Contents

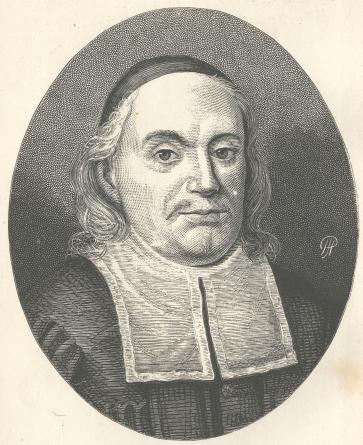

Paul Gerhardt -- P. 202 |

CHRISTIAN SINGERS

OF

GERMANY

BY

CATHERINE WINKWORTH

|

MACMILLAN & CO

PUBLISHERS

Electronic Edition

featuring

Comprehensive Indexes

PREFACE.

The hymns of Germany are so steadily becoming naturalized in England that English readers may be glad to know something of the men who wrote them, and the times in which they had their origin. Scarcely one of the numerous hymn-books which have been compiled here within the last fifteen years is without its proportion--sometimes a considerable proportion--of German hymns. This is, in fact, one of the many ways in which the literature of each nation now tends to become, through the medium of translations, the common property of both. But hymns form only a part, though an important part, of the religious poetry of Germany, which itself constitutes but one sharply defined branch of the general literature of the country. Yet it is impossible to trace the course historically of even this one channel of national expression, without being brought into contact with those great movements which have stirred the life of the people, and finding the passing fashions of each successive age, in thought or phraseology, reflected from its surface. Such a work as the present cannot attempt more than an outline of a subject which is thus linked on the one side to the general history and iv literature of Germany, while on the other it has a separate history of its own, full of minute and almost technical details. Only the principal schools and authors are described, and specimens are selected from their works; but other writers of secondary rank are mentioned, to enable readers who may be inclined to do so, to fill up the picture of any particular school or period more completely for themselves. The choice of the specimens has been determined partly by their intrinsic merits, partly by their novelty to the English public; hence nearly all the great classical hymns are named as illustrating the spirit of certain times, but they are not given in full, because they have been previously translated, and are in many instances familiar to us already. A very few, which it was impossible to pass over, form the only exceptions to this rule.

In reading the poems scattered through the following pages, it must be remembered that they suffer under the disadvantage of being all translations and from one hand, which inevitably robs them of somewhat of that variety of diction which marks, in the original, the date of the composition or the individuality of the author. Still, as far as possible, their characteristic differences have been carefully imitated, and the general style and metre of the poem retained. Verses have been occasionally omitted for the sake of brevity, and once or twice a Trochaic metre has been altered into an Iambic, where the change did not seriously affect the shape of the poem, whilst it enabled the English version to reproduce certain v striking expressions in the German. Single rhymes have been throughout substituted for double ones, cxcept where the latter constitute an essential element of the metre; this modification necessitates the addition or the omission of a syllable in the line, but makes it possible to give a more faithful and spirited rendering than can be managed within the very limited range of English dissyllabic rhymes. The frequent recurrence of particular phrases and rhymes is not accidental, but is a peculiarity of all German popular poetry from the Niebelungen Lied downwards. Besides the specimens given in this volume, many of which are rather poems than hymns, between three and four hundred German hymns in English dress may now be found in various collections of translations. Of these the chief are "Hymns from the Land of Luther;" "Sacred Hymns from the German" by Miss Cox; the "Spiritual Songs of Luther" and "Lyra Domestica" of Mr. Massie; "Hymns for the Church of England" by Arthur Tozer Russell; the "Lyra Germanica" [and the "Second Series"] and the "Chorale Book for England." Nearly all the German hymns in our ordinary hymnbooks are drawn from some one of these sources or from John Wesley. Where only the first English line is mentioned in this work, the complete hymn may generally be met with in the "Lyra Germanica," or is one of Wesley's well-known versions.11[The electronic edition includes hyperlinks in such cases.]

It seems out of place in a work like this to give a list of authorities, which would necessarily be long. German hymns, like our own, have undergone many revisions, and are to be met with in very varying vi forms; of course these specimens have been taken from what appeared to me the most trustworthy sources at my command. But I may be allowed to express my obligations to the following important works:--Wackernagel's great work, "das Deutsche Kirchenlied," both in the edition of 1842 and the one now in progress; his lives and editions of Heermann and Gerhardt, and his brother's "Altdeutsches Lesebuch;" the "Geschichte des Kirchenliedes und Kirchengesanges," by Dean Koch of Wurtemberg, to which I owe many details of the biographies of the chief hymn writers; the "Geistliche Volkslieder" of Hommel; Von Hagenbach's "Kirchengeschichte," Gervinus' "Geschichte der deutschen Dichtung;" and Gustav Freitag's charming series of sketches of German life, "Bilder aus der deutschen Vergangenheit."

CLIFTON, April 1869.

| CONTENTS. | |

|---|---|

| PAGE | |

| Of all the joys that are on earth Vor allen Freuden auf Erden--LUTHER. | 1 |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| THE EARLY DAWN OF GERMAN SACRED POETRY AND SONG. A.D. 800-900 | 3 |

| Now warneth us the Wise Men's fare Manot unsih thisu fart--OTFRIED. | 17 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| A LONG TWILIGHT. A.D. 900-1100 | 21 |

| Our dear Lord of grace hath given Unsar trohtîn hât farsalt--IX. Century. | 28 |

| Thou heavenly Lord of Light Du Himilisco trohtîn--X. Century. | 29 |

| God, it is Thy property Got thir eigenhaf ist--IX. Century. | 29 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| THE MORNING. A.D. 1100-1250 | 30 |

| Christ the Lord is risen Christus ist erstanden--ANON. | 37 |

| Now let us pray the Holy Ghost Nu biten wir den heiligen geist--ANON. | 38 |

| All growth of the forest Wurze des waldes--SPERVOGEL. | 38 |

| He is full of power and might Er ist gewaltic unde Starc--SPERVOGEL. | 39 |

| viiiO Rose, of the flowers I ween thou art fairest Diu rose ist die schoeneste under alle--DER MEISSENAERE. | 41 |

| My joy was ne'er unmixed with care Min fröede wart nie sorgelos--HARTMANN VON DER AUE. | 42 |

| Now in the name of God we go In Gotes namen faren wir--ANON. | 43 |

| E'er since this day the cross was mine Des tages do ich daz kriuze nam--REINMAR VON HAGENAU. | 44 |

| Alas! for my sorrow O wê des smerzen--ANON. | 45 |

| When the flowers out of the grass are springing So die bluomen uz dem grase dringent--WALTER VON DER VOGELWEIDE. | 46 |

| Would ye see the lovely wonder Muget in schowen waz dem meien--W. V. D. VOGELWEIDE. | 47 |

| Ye should raise the cry of welcome Ir sult sprechen willekomen--W. V. D. VOGELWEIDE. | 48 |

| In safety may I rise to-day Mit saelden müeze ich hiute ûf steh--W. V. D. VOGELWEIDE. | 50 |

| Lord God, if one without due fear Swer âne vorhte, herre Got--W. V. D. VOGELWEIDE. | 50 |

| How seldom praise I Thee, to whom all lauds belong Vil wol gelobter Got wie selten ich dich prîse--W. V. D. VOGELWEIDE. | 51 |

| Now at last is life worth living Nu alrest leb ich mir werde.--W. V. D. VOGELWEIDE. | 51 |

| Sir Percival. Eight extracts Parzival, WOLFRAM VON ESCHENBACH--(übersetzt von San Marte.) | 60 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| DARK TIMES AND BRIGHT TIMES. A.D. 1253-1500 | 69 |

| From outward creatures I must flee Ich müz die creaturen fliehen--TAULER. | 74 |

| O Jesu Christ, most good, most fair O Jesu Christ, ein lieblichz gut--TAULER. | 75 |

| My joy is wholly banished Min vreude ist gar zergangen--FRAUENLOB. | 78 |

| Now will I nevermore despair of heaven Nu wil ich nimmer mer verzwifeln--FRAUENLOB. | 80 |

| A ship comes sailing onwards Es komt ein schif geladen--TAULER. | 84 |

| A spotless Rose is blowing Es ist ein Ros entsprungen--ANON. | 85 |

| There went three damsels ere break of day Es giengen drî frewlîn also frü--ANON. | 85 |

| ixRejoice, dear Christendom, to-day Nu frew dich liebe Christenheit--ANON. | 87 |

| So holy is this day of days Also heilig ist der Tag--ANON. | 89 |

| Fair Spring, thou dearest season of the year Du lenze gut, des jares teureste quarte--CONRAD VON QUEINFURT. | 88 |

| O world, I must forsake thee O Welt, ich muz dich lassen--ANON. | 91 |

| I would I were at last at home Ich wolt daz ich daheime wer--LOUFENBURG. | 92 |

| Ah! Jesu Christ, my Lord most dear Ach, lieber herre Jesu Christ--LOUFENBURG. | 93 |

| In dulci Jubilo, sing and shout, all below In dulci Jubilo, singet und seid froh--ANON. | 94 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| LUTHER AND HIS FRIENDS. A.D. 1500-1580 | 98 |

| I've ventured it of purpose free Ich hab's gewagt mit Sinnen--ULRICH VON HUTTEN. | 99 |

| A sure stronghold our God is He Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott--LUTHER. | 110 |

| Dear Christian people, now rejoice Nun freut euch liebes Christen gemein--LUTHER. | 112 |

| In peace and joy I now depart Mit Fried und Freud ich fahr dahin--LUTHER. | 114 |

| If God were not upon our side Wo Gott der Herr nicht zu uns hält--JUSTUS JONAS. | 117 |

| I fall asleep in Jesu's arms In Jesu Wunden schlaf ich ein--PAUL EBER. | 121 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| HYMNS OF THE REFORMATION. A.D. 1520-1600 | 122 |

| Salvation hath come down to us Es ist das Heil uns kommen her--SPERATUS. | 123 |

| What pleaseth God, that pleaseth me Wie's Gott gefällt, gefällt's mir auch--BLAURER. | 124 |

| Grant me, Eternal God, such grace Genad' mir Herr, Ewiger Gott--MARGRAVE OF BRANDENBURG. | 125 |

| Awake, my heart's delight, awake Wach' auf meines Herzens Schöne--HANS SACHS. | 131 |

| O Christ, true Son of God Most High Christe, wahrer Sohn Gottes frohn--HANS SACHS. | 134 |

| xPraise, glory, thanks be ever paid Lob und Ehr mit stettem Danckopfer--BOHEMIAN BRETHREN. | 137 |

| Lord, to Thy chosen ones appear Erscheine allen auserwählten--BOHEMIAN BRETHREN. | 139 |

| Now God be with us, for the night is closing Die Nacht ist kommen drinn wir ruhen sollen--BOHEMIAN BRETHREN. | 139 |

| When my last hour is close at hand Wenn mein Stündlein vorhanden ist--NICOLAS HERMANN. | 143 |

| O Father, Son, and Holy Ghost O Vater, Sohn, und Heil'ger Geist--MATTHESIUS. | 144 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| AN INTERVAL. A.D. 1560-1616 | 146 |

| Lord Jesu Christ, my Highest Good Herr Jesu Christ, mein höchstes Gut--RINGWALDT. | 149 |

| Lord Jesu Christ, with us abide Ach bleib bei uns, Herr Jesu Christ--SELNECKER. | 152 |

| Make me Thine own and keep me Thine Lass mich dein sein und bleiben--SELNECKER. | 152 |

| From God shall nought divide me Von Gott will ich nicht lassen--HELMBOLDT. | 154 |

| In God, my faithful God Auf meinen treuen Gott--WEINGARTNER. | 156 |

| Thou burning Love, Thou holy Flame Brennende Liebe, du heilige Flamme--ANON. | 157 |

| O Morning Star, how fair and bright! Wie schön leuecht't uns der Morgenstern--NICOLAI. | 160 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| THE THIRTY YEARS' WAR. A.D. 1618-1650 | 165 |

| O Light, who out of Light wast born O Licht geboren aus dem Lichte--OPITZ. | 173 |

| Let nothing make thee sad or fretful Lass dich nur nichts nicht dauern--FLEMMING. | 175 |

| Can it then be that hate should e'er be loved Ist's möglich, dass der Hass auch kann geliebet sein?--FLEMMING. | 175 |

| All glories of this earth decay Die Herrlichkeit der Erden--GRYPHIUS. | 177 |

| In life's fair spring In meiner ersten Blüt'--GRYPHIUS. | 179 |

| Now thank we all our God Nun danket alle Gott--RINKART. | 181 |

| xiO ye halls of heaven Schöner Himmelssaal--S. DACH. | 185 |

| Worthy of praise the Master-hand Der Meister ist ja lobenswerth--ROBERTHIN. | 187 |

| O darkest woe! ye tears forth flow O Traurigkeit, O Herzeleid--JOHANN VON RIST. | 191 |

| Now God be praised, and God alone Gott sei gelobet der allein--J. VON RIST. | 192 |

| Ah, Lord our God, let them not be confounded Herr unser Gott, lass nicht zu Schanden werden--J. HEERMANN. | 197 |

| Zion mourns in fear and anguish Zion klagt mit Angst und Schmerzen--J. HEERMANN. | 198 |

| Jesu, Saviour, since that Thou Jesu, der du bist, mein Heil--J. HEERMANN. | 200 |

| Thou loving Jesu Christ Du süsser Jesu Christ--J. HEERMANN. | 200 |

| Jesu, who didst stoop to prove Jesu der du tausend Schmerzen--J. HEERMANN. | 200 |

| Jesu, Victor over sin Jesu, Tilger meiner Süden.--J. HEERMANN. | 201 |

| That Death knocks at my door, too well Der Tod klopft an bei mir, dass--J. HEERMANN. | 201 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| PAUL GERHARDT AND HIS CONTEMPORARIES. A.D. 1620-1680. | 202 |

| Hence, my heart, with such a thought Weg mein Herz mit dem Gedanken--PAUL GERHARDT. | 210 |

| To God's all-gracious heart and mind Ich hab' ergeben Herz und Sinn--P. GERHARDT. | 213 |

| Full of wonder, full of art Voller Wunder, voller kunst--P. GERHARDT. | 215 |

| I will return unto the Lord Ich will von meiner Missethat--ELECTRESS LOUISA. | 221 |

| Patience and humility Wer Geduld und Demuth liebet--ANTON ULRICH. | 225 |

| Jesu, priceless treasure Jesu meine Freude--JOHANN FRANK. | 228 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| THE NEW SCHOOL. A.D. 1635-1700 | 230 |

| Aphorisms by FRIEDRICH VON LOGAU Sinn sprüche von SALOMON VON GOLAW. | 232 |

| xiiReader, dost thou seek to know Leser, möchtest du erkennen--LOGAU. | 233 |

| Generous Love, why art thou hidden so on earth Edele Lieb, wie bist du hier so gar verborgen--ANDREA. | 235 |

| The gloomy winter now is o'er Der trübe Winter ist vorbei--SPEE. | 242 |

| Thou Good beyond compare Du unvergleichlich Gut--ANGELUS. | 249 |

| Morning-star in darksome night Morgenstern in finst'rer Nacht--ANGELUS. | 251 |

| Aphorisms by ANGELUS Sinnsprüche von ANGELUS SILESIUS. | 252 |

| Jesu, be ne'er forgot Jesu, gieb uns dein' Gnad--ANON. | 255 |

| Why is it that life is no longer sad Woher denn kommt' es zu dieser Zeit--ANON. | 255 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| THE PIETISTS. A.D. 1660-1750 | 256 |

| Thou art First and Best, Jesu, sweetest Rest Wer ist wohl wie du, Jesu süsse Ruh--FREYLINGHAUSEN. | 267 |

| Shall I o'er the future fret Sollt' ich mich denn täglich kränken--SPENER. | 270 |

| Jehovah, God of boundless strength and might Jehovah, hoher Gott, von Macht und Stärke--BOGATZKY. | 274 |

| Courage, my heart, press cheerly on Frisch, frisch hindurch, mein Geist und Herz--DESSLER. | 277 |

| Thou fathomless Abyss of Love Abgrund wesentlicher Liebe--P. F. HILLER. | 281 |

| Bed of sickness! thou art sweet Angenehmes Alrankenbette--P. F. HILLER. | 283 |

| O Thou true God alone Unbegreiflich Gut, wahrer Gott alleine--JOACHIM NEANDER. | 286 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| THE MYSTICS AND SEPARATISTS. A.D. 1690-1760 | 289 |

| Anoint us with Thy blessed Love Salb' uns mit deiner Liebe--GOTTFRIED ARNOLD. | 293 |

| Full many a way, full many a path Gar mancher Weg, gar manche Bahn--G. ARNOLD. | 295 |

| I leave Him not, who came to save Ich lass Ihn nicht, der einst gekommen--G. ARNOLD. | 296 |

| xiiiLost in darkness, girt with dangers--GERHARD TERSTEEGEN. Extract from Jesu, mein Erbarmer, höre. | 298 |

| I lose me in the thought Wo find ich mich--G. TERSTEEGEN. | 302 |

| Out! out, away! Aus, aus, hinaus--G. TERSTEEGEN. | 303 |

| Within! within, O turn Hinein, hinein--G. TERSTEEGEN. | 303 |

| Lovely, shadowy, soft, and still Lieblich, dunkel, sanft und stille--G. TERSTEEGEN. | 304 |

| To praise the Cross while yet untried Das Kreuz zu rühmen weun es fern.--G. TERSTEEGEN. | 304 |

| Nay! not sore the Cross's weight Nein, das Kreuz hat keine Last--G. TERSTEEGEN. | 304 |

| Ah God! the world hath nought to please Ach, Gott, es taugt doch draussen nicht--G. TERSTEEGEN. | 304 |

| Jesu, day by day Jesu, geh voran--ZINZENDORF. | 309 |

| Such the King will stoop to and embrace Solche Leute will der König küssen--ZINZENDORF. | 310 |

| Lamp within me! brightly burn and glow Brenne hell du Lampe meiner Seele--ALBERTINI. | 311 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| MODERN TIMES. A.D. 1750-1850 | 313 |

| When these brief trial-days are spent Nach einer Prüfung kurzer Tage--GELLERT. | 318 |

| O ye, who from your earliest youth Die ihr, des Lebens edle zeit--CRAMER. | 321 |

| Trembling I rejoice Zitternd freu' ich mich--KLOPSTOCK. | 329 |

| Round their planet roll the moons Um Erden wandeln Monde--KLOPSTOCK. | 332 |

| Rise again! yes, rise again wilt thou Aufterstehn, ja aufterstehn wirst du--KLOPSTOCK. | 333 |

| At dead of night sleep took her flight Um Mitternacht bin ich erwacht--RÜCKERT. | 337 |

| In Bethlehem the Lord was born Er ist in Bethlehem geboren--RÜCKERT. | 338 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

"A PREFACE TO ALL GOOD HYMN-BOOKS."

Lady Musick speaketh.

Vor allen Freuden auf Erden

|

CHAPTER I.

THE EARLY DAWN OF GERMAN SACRED POETRY AND SONG.

A. D. 800-900

Each Christian people has brought its own characteristic tribute to the vast treasury of devotional thought and literature, which is the common property of the whole Christian Church. The tribute of Germany is pre-eminently that of sacred song, of verse and music in combination and adapted for use in the Church and among the people. Her literature begins with a work of religious poetry, and from that time onwards has been always remarkably rich in productions of this class. The very genius of the people--its inborn love for music, especially for part-singing, its bent towards the expression of feeling in the lyrical form--peculiarly fitted it for this work; and the result has been the creation of a literature of hymns and hymn-tunes, which has had a wide influence not only within but beyond Germany. The hymn-books of Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Iceland, and in part those of Holland, consist, to a large extent (until recently it would have been correct, we believe, to say, almost entirely), of translations and adaptations from the German; which have, however, become so completely 4 naturalized among the people that their alien origin is forgotten, and they have furnished the model on which the hymns of native growth have been composed. In Switzerland, in the Protestant Church of France, and to some extent in Holland, the spread of the German hymns has been checked by the influence of the Calvinistic Churches, which have always feared to give a prominent place to art of any kind in the worship of God--rather indeed have allowed it to creep in on sufferance, than delighted to introduce it as a free-will offering of beauty. Yet here, too, hymns adopted from the German, or of the German type, have gradually made their way. In England the national character of our Reformation has left less scope for the influence of foreign elements. Our Church has distinguished its services more by the beauty of its prayers than its hymns, while our Nonconformist sects have been strongly imbued with those Calvinistic views of worship of whose influence we have just spoken. But a people with so marked a genius for poetry as the English, could not but use their gift in the service of religion as well as in secular ways; though the fact that hymns occupied a less important place in the religious worship of England than Germany, produced a marked difference in form in the compositions of the two countries. Germany's preeminence is in her hymns; but in sacred poetry not of this class, she has had no names of equal rank with those of Milton or Herbert of old, or Keble, Coleridge, and Wordsworth in the present day. In course of time, however, her hymns reached us too. There can be no doubt that the acquaintance of the Wesleys with the stores of her hymnology led them to see both the 5 beauty of this form of poetry and the immense advantages that might be drawn from it, in spreading a knowledge of the truth among the common people, and in increasing the warmth and attractiveness of worship. They not only translated many German hymns, but wrote a large number themselves in the same style; and it is from their time that the impulse dates which has led to the study of hymnology, not only of English or German, but also of Latin and Eastern growth, and to the rise among us of a large number of new and very good hymn-writers and hymn-books.

The story of the hymnology of Germany in the sense we have here given it, begins properly speaking with the Reformation. It was not until the people possessed the word of God and liberty to worship Him in their own language, that such a body of hymns could be created, though vernacular hymns and sacred lyrics had existed in Germany throughout the Middle Ages. But it was then that a great outburst of national poetry and music took place which reflected the spirit of those times; and on a somewhat smaller scale the same thing has happened both before and since that time at every great crisis in the history of the German people. The most marked of these periods are the twelfth and thirteenth centuries--the era of the Crusades abroad and the rise of the great cities at home; the Reformation; the great struggle for religious liberty in the seventeenth century; and the revival of literature towards the close of the eighteenth century, after the exhaustion that followed the Thirty Years' War.

As far back, however, as we hear anything of the 6 German race, we hear of their love for song. They sang hymns, we are told, in their heathen worship, and lays in honour of their heroes at their banquets; and their heaven was pictured as echoing with the songs of the brave heroes who had fallen in battle. The first dawn of Christianity came to the Gothic races from Greece, but in Southern Germany it seems to have proceeded from the many missionaries who were sent out by the British and Irish monasteries in the sixth century, who sought no special authorization from Rome, and did not carry with them the Roman liturgy. But the chief instruments in the conversion of the remoter regions were the Anglo-Saxon monk Winifred, better known as St. Boniface, who was martyred in 755, and Charlemagne. Both these great men saw the imperative need of some centre of unity and order to restore society and preserve anything of faith or of letters in those times of utter chaos and discord, and believed that they had found the means to this end in the unity of the Church. That they greatly promoted civilization there is no doubt, but their work, even that of Boniface, had its darker side, where it came in contact with an already existing Christianity, and forcibly repressed what was national and distinctive in its character. For wherever they went they introduced at once not only the Christian religion, but the hierarchy and liturgy of Rome, and with it the Gregorian Church music and the Latin hymns.

Ambrosian Church Music

This style of music owes its origin to Pope Gregory the Great, who ascended the papal chair in 590, and thenceforward devoted his extraordinary abilities and energy to securing the unity and independence of the 7 Church. Here, however, we are only concerned with his influence on Church music. Before his time the Ambrosian style had been widely prevalent through the Western Church. It was founded on the Greek system of music, and was introduced by St. Ambrose, with the assistance of Pope Damasius, into the Great Church of Milan in the year 386. A true instinct taught St. Ambrose to adopt for his hymns the most rhythmical form of Latin verse that was then in use, and for his tunes a popular and congregational style of melody, and thus both spread rapidly through the Western Church, and became a powerful engine for affecting the minds of the people of all classes. In a well-known passage of his "Confessions,"22Library of the Fathers. St. Augustine's "Confessions," p. 166. St. Augustine tells us (he is addressing our Lord):--"How did I weep, in Thy Hymns and Canticles, touched to the quick by the voices of Thy sweet-attuned Church! The voices flowed into my ears, and the Truth distilled into my heart, whence the affections of my devotion overflowed, and tears ran down, and happy was I therein. Not long had the Church of Milan begun to use this kind of consolation and exhortation, the brethren zealously joining with harmony of voice and hearts. For it was a year, or not much more, that Justina, mother to the Emperor Valentinian, a child, persecuted Thy servant, Ambrose, in favour of her heresy, to which she was seduced by the Arians. The devout people kept watch in the Church, ready to die with their bishop, Thy servant. Then it was first instituted that after the manners of the Eastern Churches, hymns and psalms should be sung, lest the people should wax 8 faint through the tediousness of service; and from that day to this the custom is retained, almost all The congregations throughout other parts of the world following herein."

One tune from the Ambrosian period is still preserved in Germany to the present day, in connexion with Luther's German version of St. Ambrose's great hymn, Veni Redemptor gentium. It is a simple, dignified, somewhat quaint melody.33It may be found in German tune-books under the name of "Nun kommt der Geidenheiland," and is No. 72 in the Chorale-Book for England.

In course of time, however, there is no doubt that Church music had become deteriorated by the introduction of a more secular style, and that this was one cause of the reaction under Gregory the Great. Yet another may perhaps be found in the fact that the Ambrosian style was an intrinsically congregational method of singing, which enabled all the people to bear a part, and not a small one, in the service; while the Gregorian, which had less melody and rhythm, and was extremely difficult to acquire, was necessarily restricted to the clergy and the trained choir, and therefore harmonized better with the hierarchical principles of Gregory.

Gregorian Church Music

It was natural, therefore, that from this period onwards, as the hierarchical element in the Church gained strength, this system should have rapidly supplanted its rival; nor would it be fair to say that this was altogether without its advantage, for in those distracted times the impulse towards unity in the Church was in many ways a true instinct towards self-preservation, and a common liturgy is one of the strongest bonds of a common 9 religious life. There is, too, undoubtedly much grandeur and beauty in this style, which adapt it for certain forms and occasions of worship; but its stiffness and monotony, and its aptness to degenerate into a nasal unmusical chant in the hands of untrained singers, unfit it for truly popular and common use. It has maintained its place in the Roman Church to the present day, and has exerted a strong influence on the music of the reformed Churches. During the eighteenth century this influence showed itself markedly in Germany in the adoption of a certain slow and uniform style of singing the old chorales, admitting only notes of equal length, and in "common" time. Recently there has again been a reaction towards the freer and more varied rhythm of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when the laity delighted to assert their right to a share in the Christian priesthood, by bearing a part in the public service of God.

One thing that helped to make the Gregorian chanting an affair of the learned, was the very complicated method of notation then employed, and it was soon found necessary to establish schools, in which singers went through a training that lasted often for years. Gregory founded a famous school in Rome, with a prior and four masters, and for many generations afterwards the sofa was shown on which he used to recline while himself examining the scholars. They were mostly orphan boys who were entirely maintained here, and afterwards received appointments from the Pope. In the days of King Ethelbert, forty of them came to England, and introduced the Gregorian music into this country.

10Charlemagne, like our own Alfred, was an enthusiastic lover of Church music, and especially of this style which he had learnt to know in Rome. In his own chapel he carefully noted the powers of all the priests and singers, and sometimes acted as choir-master himself, in which capacity he proved a very strict, often severe master, He extinguished the last remnants of the Ambrosian style at Milan, and it was with his approval that Pope Leo III. (795-810) imposed a penalty of exile or imprisonment on any singer who might deviate from the orthodox Cantus firmus et choralis. He not only founded schools of music in France, but throughout Germany, at Fulda, Mayence, Treves, Reichenau, and other places. Trained singers from the famous choirs in Rome were sent for to take charge of these institutions, and seem to have been not a little shocked at first by the barbarism of their pupils. One says that their notion of singing in Church was to howl like wild beasts; while another, Johannes Didimus, in his Life of Gregory, affirms that--"These gigantic bodies, whose voices roar like thunder, cannot imitate our sweet tones, for their barbarous and ever-thirsty throats can only produce sounds as harsh as those of a loaded waggon passing over a rough road."

A Benedictine Monastery

The new style of Church music naturally found its most zealous promoters in the cloisters, among whom we may name Rabanus Maurus, a pupil of Alcuin, and abbot of the great convent of Fulda, and Walafrid (nicknamed Strabo), abbot of Reichenau. The Benedictine monasteries which were henceforward founded in increasing numbers north of the 11 Alps, were for the next two or three centuries, the asylums where arts and letters were preserved through the storms of those stormy times. Every convent, in fact, constituted a little town in itself when it had attained its full proportions. It began generally in the humblest manner. The abbot of some considerable monastery would send a small band of missionary monks to some spot, chosen either for its natural advantages, or from the needs, or perhaps the earnestly-expressed wishes, of the surrounding population. First, the monks would fell the trees, and erect temporary huts for themselves; then the chapel was built and service celebrated; then more permanent abodes were constructed, and gardens and fields were brought into cultivation. Then, if possible, the relics of some saint were procured, and deposited within the altar to give a special sanctity to the place, and attract worshippers in the hope of obtaining miraculous cures, and henceforward the number of monks and dependants would rapidly increase. When the institution was completed, we know by plans still preserved in the archives of St. Gall, that it would consist of the church as centre, the monks' dwellings, the cloisters, and the convent school within the inner inclosure; around which clustered handsome buildings for the abbot's and physician's houses; for the secular school, the hospital, the lodgings for travellers, whether monks or laymen; and the smaller abodes and workshops necessary for the various artificers whose crafts here found employment. The whole of this little town, so to speak, was itself inclosed within a ditch, and in later times fortified with walls and towers.

12Notker's Sequences

Among the most complete and famous of these monasteries was that of St. Gall. In that lonely but sheltered spot on the lower slopes of the Alps, and not far from Lake Constance, which gave access to Southern Germany, there was cherished for centuries a sacred fire of true enthusiasm for learning, which spread its light by degrees into many a half-barbarous court and distant convent. Here the earliest and most strenuous efforts were made to tame the rough mother-tongue of the Germans, and teach it to express as far as might be the shades of thought and feeling which the languages of Greece and Rome had so marvellously embodied, and all that the Christian faith had to say besides. There exists in its archives a very ancient Latin and German dictionary traditionally ascribed to St. Gall himself (died 638), and many other glossaries, paraphrases, and interlinear translations from the Latin. Among those who thus occupied themselves in the ninth century was a monk named Notker, whom Walafrid, then Dean of St. Gall's, strongly urged to devote himself to sacred poetry. He wrote, however, in Latin, and his hymns therefore concern our subject only because he was the originator of a form of Latin hymnology, which when translated into German gave rise to the earliest German hymns, properly so called, with which we are acquainted. This was the Latin Sequence or Prose. It was customary in all cases where a Hallelujah was introduced to prolong the last syllable, and to sing on the vowel "ah" a series of elaborate passages intended to represent an outburst of jubilant feeling. These were termed Sequences, because they followed the Hallelujah and repeated its notes, 13 and were of course sung without words. What Notker did was to write words for them, and he tells us himself how he came to do it, in a letter addressed to Bishop Luitward, to whom he dedicated a volume of these compositions. "When I was yet young and could not always succeed in retaining in my memory the long-drawn melodies on the last syllable of the Hallelujah, I cast about in my mind for some method of making them easier to remember. Now it happened that a certain priest from Gimedia came to us who had an Antiphonarium, wherein were written some strophes to these melodies, but indeed by no means free from faults. This put it into my mind to compose others for myself after the same manner. I showed them to my teacher, Yso, whom they pleased on the whole, only he remarked, that as many notes as there were in the music, so many words must there be in the text. At this suggestion I went through my work again, and now Yso accepted it with full approbation, and gave the text to the boys to sing." These Sequences spread rapidly, for they supplied the want that was beginning to be felt of melodies in which sometimes the people could join, and words which could be adapted to special occasions beyond the ordinary service of the mass. They increased in number therefore more quickly than the hymns properly so called, and gradually assumed a strictly metrical form, which at first they did not possess. Notker himself composed thirty-five of them; and one which still finds a place in our own Burial Service, the "Media vita in morte," is traditionally ascribed to him, and said to have been written while watching some workmen building 14 the bridge of St. Martin at the peril of their lives. It cannot however be certainly traced beyond the eleventh century, but from that time onwards it was in use in the Latin, and afterwards in a German version as a battle-song, which was supposed to exert magical influences.

The Heliand

It is to this same ninth century, and in one instance, to the teachings of the convent of St. Gall, that we owe the two earliest specimens of German sacred poetry. They are both Harmonies of the Gospels, and it strikingly shows the affinity of the Teutonic mind for the Jewish Scriptures, that the earliest monuments of its written literature are all drawn from this source--the translation of the Bible into Gothic by Ulphilas, the great Bishop of the Goths, who died in 388, and the two books now before us. The earliest of them is called "The Heliand," or the Saviour, and is written in Saxon, therefore in the ancient Low German dialect. It is said to have been suggested by Louis the Pious to teach the newly-converted Saxons something of the faith they had accepted, and to have been carried out by a peasant who heard in his sleep a voice summoning him to the undertaking. About thirty years later, a similar task was achieved by Otfried, a monk probably of Alemannic race, who had been educated at first at Fulda under Rabanus Maurus, then had lived many years in St. Gall, and finally removed to Weissenburg in Alsace, another of the numerous monasteries scattered along the border of Switzerland, where the mountains break down to the lakes and cultivated country of Northern Europe. Though they thus belong to the same period of time, these works were composed under widely different 15 circumstances. In Southern Germany the Romans had founded large cities, and Roman and Celtic elements were mingled with the Teutonic blood. Christianity had early made its way there, and a considerable amount of it existed before the earliest missionaries from Rome came thither. In the seventh century St. Emmeran found a multitude of priests and churches in Bavaria; the land had already gloried in several native saints before the time of Charlemagne; and culture must have made no inconsiderable progress, when we are told that the noble lady Theudelinde was able to maintain a pious and learned correspondence with Pope Gregory the Great. In Northern Germany, on the other hand, little had been done for the introduction of Christianity until Charlemagne converted the people by force, and the country long remained scantily populated and unsettled. Vast tracts of forest or heath were interrupted by solitary farmsteads of immense extent, where cattle and sheep were the chief source of wealth; for, until the close of the tenth century, there was but little agriculture; towns and monasteries existed but in small numbers and at great distances, and it was long before any churches except the convent chapels were built. Slowly the new religion permeated this wild and scattered people; but as it did so, it rooted itself the more deeply in the popular life, and bore less of the impress of the hierarchical and Roman element than the religion of Southern Germany, a distinction which has maintained itself even to the present day.

The form of the two works is contrasted as we might expect from their origin; the Heliand is written 16 in the alliterative measure of the ancient ballads, but without strophes; the work of Otfried is composed in four-lined verses with rhyme. Rhyme is a peculiarly Christian ornament of verse, and the struggle was long between accented and rhymed forms of poetry, and the ancient forms of classical metre. Otfried's is the first rhymed poem we possess, and thus has always marked an important epoch in European literature. The Heliand is not so much a Harmony of the Gospels as a Saxon epic on the life of our Lord, and it seems to have been intended to form part of a larger work embracing the whole course of Scripture History. The style is simple and naïve: the writer nowhere brings forward his own personality, but is evidently inspired by a strong love to his subject. The relation of the disciples, and implicitly the relation of all Christians to their Lord, is conceived after the true Teutonic type as that of followers bound by an oath to their duke or leader; all that expresses personal loyalty and obedience on the one hand, or affectionate condescension on the other, is brought out with quick insight and strong feeling. In general, the writer keeps very close to his authorities, but in some passages, where the heathen lays may have been recalled to his mind, he permits himself a more excursive description, and echoes of the old Scandinavian ballads float through his verse. The Sermon on the Mount specially attracts him, and he gives it with fulness and evident predilection.

Otfried of Weissenburg

Otfried, on the other hand, continually betrays his acquaintance with classical models, and the self-consciousness of the educated barbarian in the presence of a higher culture. He is constantly 17 lamenting his own incompetence and the barbarism of the German tongue; he gives fewer facts and less of the distinctly ethical discourses than his Saxon contemporary; but he much more frequently introduces episodes, sometimes similes or allegories from ecclesiastical works, sometimes mystical and moral reflections of his own. But there are passages where he rises to warmth and true poetry, as where, in describing the journey of the Magi, he speaks of the longing of the soul for its heavenly fatherland; and the very idea of thus endeavouring to make the grounds of their faith intelligible to the common people, marks him out as no common man.

The following is a version of the passage just mentioned. The rhyme and metre of the original are very irregular, and here and there a rhyme is wanting altogether; still, as its structure constitutes a marked difference between this poem and its predecessors, it seemed best to imitate, as far as possible, its rhythm, while keeping close to the meaning; but in such a process somewhat of the poetical element is apt to vanish.

MYSTICE DE REVERSIONE MAGORUM AD PATRIAM.

Manot unsih thisu fart

|

CHAPTER II.

A LONG TWILIGHT.

A.D. 900-1100.

Barbarian Incursions

The two centuries we have now reached are a very barren period for literature. Charlemagne had given an impulse to arts and letters of which the effects are traceable as long as there were any pupils left of the circle of learned men whom he gathered round his court. But these gradually died out, and his vast empire fell to pieces. Then came a time when men had something else to do than to read or write; had too often to fight or flee for their lives to have much leisure or thought for more peaceful tasks. The frontiers of Germany had to be secured, its lands brought under cultivation, its towns built, its social polity developed. It was not until the great defeat of the Normans in 891 by Arnulf, at Loven on the Dyle, that Germany was delivered from their attacks, and its eastern portion was kept in constant alarm by the incursions of the Hungarian and Slavonic tribes, until nearly the close of the eleventh century. Thus on one occasion, early in this century, the whole of Germany between the Elbe and the Oder was ravaged; the most horrible cruelties were practised, especially against monks and priests, and all the churches were burnt down. The 22 cause of offence was that the chief had asked in marriage the daughter of the Duke of Saxony, and had received the scornful reply that it was not meet to give a Duke's daughter to a dog,--a play on the words Hun and Hund, or hound.

A vivid description of one of these incursions is left us by Eckhard IV., a monk and chronicler of St. Gall. In the year 924, an invasion of the Hungarians took place, which lasted for two years. The wild hordes first burst into Bavaria, swept over all the south of Germany, and then vanish from our story as they pass down the Rhine. They carried with them cattle and carts containing their plunder. At night they placed their carts in a circle, lit watch-fires, and stationed watchmen outside the barrier, while within it they encamped on the ground. By day they ravaged the country, plundering and burning on all sides; so that their approach was heralded by the red glare of burning villages on the horizon. When the abbot of St. Gall heard of them, he assembled the brethren and all the dependants, and commanded that they should at once begin to make spears, and shields, and other weapons, and also prepare a fortified asylum in case of attack. He himself and the other monks put on their coats of steel, and drew over them the monk's cloak and cowl, and laid their own hands to the work of fortifying the point he had chosen, a spot at the junction of three streams, which could only be approached by a narrow way. The monks and servants would not believe in the coming danger, and so it was but just in time that they transported their valuables to this retreat. The very next day the Huns appeared. Only two persons had 23 been left in the convent, a holy woman who had made a vow of seclusion and refused to leave her cell, and a half-witted monk who could not be induced to accompany his brethren into their fortress. The former was murdered, the latter was treated with a rough good-nature, and given as much wine and meat as he could take,--"though of a truth the discourteous people, when I had drunk enough, forced me to drink more with blows," he said afterwards. The Hungarians took all they could find, and observing that the highest point of the building, the vane, was crowned by a shining cock, they concluded this to be the god of the place, and supposed his image would be of gold. Two men therefore tried to ascend the tower and bring down the weathercock, but both fell and were killed. Their companions, enraged, next endeavoured to burn down the church, but its thick walls defied their efforts, on which they withdrew to the gardens, saying that the god was too strong for them. They then sent spies to examine the abbot's place of refuge, but these reported that its natural strength and the determination of its defenders seemed so great, that it would be best to leave it alone; and so, after a long and wild banquet in the convent gardens, the barbarians gradually drew off, and fell upon the neighbouring villages. For some weeks, however, the abbot could not venture to leave his fort, fearing their return, but every day he and some of the bolder monks stole down to the abbey, and said mass at its altar. At last he heard that the enemy was really gone. One of the suburbs of Constance had been burnt down, but the town itself and the abbey of Reichenau, 24 which had been next attacked, had been successfully defended, and the barbarians were on their way to the Rhine.

By very slow degrees these wild people were either subdued and converted to Christianity, or pressed back into the vast plains and thick forests and morasses of Central Europe, and the frontiers of Germany became at peace. But within them was constant fighting still. All the great nobles claimed the right of private war; there was no regular administration of justice; trial by ordeal was practised; and a revolt against the Emperor himself appeared to his powerful vassals the most natural thing to be undertaken when they had any grievance to avenge, or when his absence in Italy offered a fair opportunity. These early Othos and Henrys of the Saxon and Salic lines, were indeed, for the most part, men of ability and energy, who strove hard to establish order and promote civilization; but their power in the State depended almost entirely on their personal character and the wealth and consequence of their families, and was weakened by their frequent absences in Italy.

The Truce of God

In Germany itself, the clergy, on the whole, frequently sided with the Emperor as against the nobles, and to some extent thus constituted themselves protectors of the common people. They treated their dependants more mildly than other lords did, and their methods of agriculture were superior to any other; they gave employment, too, to many handicrafts, and thus it was not unnatural that towns gradually grew up or rapidly increased round the great abbeys and bishops' sees. It was to 25 two assemblies of bishops, moreover, that the distracted world owed that Truce of God, proclaimed in the year 1032, which gave breathing-time to the poor down-trodden peasant or townsman, and was the beginning of a more settled state of society. It was an agreement that no violence or weapons of any kind should be used from sunset on Wednesday to sunrise on Monday, nor on any high festival of the Church, and whosoever violated this peace was to pay his fine or wehrgeld, or suffer excommunication. Many of the nobles at first refused to submit to this, and declared their intention of adhering to the good old customs of their forefathers, and fighting on every day in the week: but a succession of bad harvests and a great dearth which occurred about this time was pointed out to them by the bishops as a sign of God's anger with their conduct; and even the turbulent Normans of France yielded to this argument. Nor indeed was it untrue, for it is evident that the local scarcities of food, which were of terribly frequent occurrence at this period, were in great measure due to the evil passions and ignorance of men. From this time onwards, however, we can trace an increase in the extent of land brought under cultivation; mining was introduced in the Harz district, and the towns steadily grew in wealth and importance. But how much of heathen superstition still lingered in the most Christian and civilized places, is curiously shown by a Mirror of Confession written by a Bishop Burchardt of Worms, early in the eleventh century. There we find penances assigned for worshipping the sun, the moon, the starry heavens, the new moon, or an eclipse, and for trying to restore the moon's light 26 when eclipsed, by wild outcries, "as though the elements could help thee, or thou couldst help them." So, too, offering prayers and sacrifices by a well, at a cross-road, or to stones is forbidden, and so is the old wives' custom at the birth of a child, of placing food and drink and three knives on the table to propitiate the Parcae or Three Sisters. The good old bishop believes in trial by ordeal, but we cannot but feel a great respect for him when we find the belief in the possibility of witchcraft and in divination classed among utterly vain and empty superstitions; and when we observe the heavy penalties affixed to slaying a bondsman even at the command or by the hand of his lord, unless he were a thief and a murderer; and to selling or entrapping any human being into slavery. To the former of these offences it seems no secular penalty was then attached, the lord possessing the power of life and death over his bondsman. Yet side by side with these superstitions there was a great deal of genuine Christian faith, among the laity as well as the clergy. The separation between these two classes was not indeed so marked as it afterwards became. Many of the secular clergy were married--Bishop Burchardt imposes a penance on any one who should despise or refuse the ministrations of a married priest,--and the monks often vied with the knights in field sports, as they did with the farmer in agriculture. When the need arose of defending land or faith by arms, the abbot raised his troops like the lord of any other fief, and could even on occasion, as we have seen at St. Gall, put on his own coat of mail and become general himself. On the other hand, many knights rivalled the monks in pious exercises, 27 and the cloister was their natural refuge when pressed by conscience or the troubles of a restless life. It was in the secular school of the convent that their children were educated, and it was among the higher clergy that the princes sought for State-advisers and secretaries.

Ezzo of Babingberg

Throughout this period the literature of Germany remained exclusively in the hands of the clergy, and was written in Latin, the then universal medium of communication for the learned class. Even so truly popular a subject as the story of "Renard the Fox" was treated in Latin, for the earliest existing MS. of it is a Latin version, which it is, however, supposed was based on a Flemish original now lost.44The earliest German version dates from 1170. This was indeed a sort of flowering time of mediaeval Latin poetry, while native German poetry was almost extinct. Only a very few German poems remain from these centuries, and these are not remarkable except for their date. The principal are two long poems, by Ezzo, a learned canon of Babingberg, on the miracles of Christ, and on the mysteries of redemption and creation.

Early Hymns

In the public services of the Church the people's share was confined to uttering the response, "Kyrie Eleison, Christe Eleison," at certain intervals during the singing of the Latin hymns and psalms. These words were frequently repeated, sometimes two or three hundred times in one service, and were apt to degenerate into a kind of scarcely articulate shout, as is proved by the early appearance, even in writing, of such forms as "Kyrieles." But soon after Notker had created the Latin Sequence, the priests began to 28 imitate it in German, in order to furnish the people with some intelligible words in place of the mere outcry to which they had become accustomed. They wrote irregular verses, every strophe of which ended with the words, "Kyrie Eleison," from the last syllables of which these earliest German hymns were called Leisen. They were, however, never used in the service of the mass, but only on popular festivals, on pilgrimages, and such occasions. The most ancient that has been handed down to us is one on St. Peter, dating from the beginning of the tenth century, of which we give an imitation, as well as we can manage it, in English; and also of a prayer from the tenth century, which is found at the close of a copy of Otfried's work, inscribed, "The Bishop Waldo caused this Evangelium to be made, and Sigibart, an unworthy priest, wrote it." The language of both differs so widely from modern German, as to be unintelligible without a glossary; but both are written in irregular metre, and in rhyme, though the rhymes are very imperfect.

ST. PETER.

i

Unsar trohtîn hât farsalt

|

PRAYER.

7,7,7,7

Du Himilisco trohtîn

|

ANOTHER PRAYER (Ninth Century).

7,7,7,7

Got thir eigenhaf ist

|

CHAPTER III.

THE MORNING.

A.D. 1100-1250

A wonderful change came over Germany during the next two centuries. There was a great change in the mere external aspect of the country. The peasant who looked out from the door of his farmstead saw a very different landscape from that which greeted his forefather's eyes. The forest indeed still skirted the horizon, but the cleared spaces were wider, and the monotonous green of the broad stretches of pasture land was broken up by the more varied colouring of arable crops. The villages were far more thickly studded over the land, and nearly every one had its wooden church with its one tinkling bell; while farther off, by the river-side, stood some great abbey with its stone buildings, round which a busy town was rapidly growing up, where the village found a market for its produce and employment for its superfluous population. But one new feature would not please the peasant quite so well: on any neighbouring height which commanded the fertile meadows beneath, there was almost sure to be perched a new stone dwelling, inhabited by some armed follower of the prince or great lord of the country, and from these 31 strongholds a lawless crew often issued to carry off the fruits of peaceful industry. During the next two hundred years, indeed, the most marked changes in the social aspect of the age were the growth of the great towns in size, wealth, political power, and all the arts of life; and the rise of a large class of armed and mounted followers of the great lords of the empire, whom the institution of chivalry placed, in a certain sense, on a level with their chiefs, while it constituted a barrier between them and the unknightly classes--an order which in after-times developed into the lesser nobility of the empire.

Frederick Barbarossa

But it was altogether an era of rapid growth, one of those times when men's minds are awake and alive, and full of energy to attempt new enterprises in any field. Germany was ruled by the Hohenstauffens, a vigorous, ambitious, warlike race, whose dream it was to prove themselves true heirs of Charlemagne by re-establishing the Empire of the West, and who fell at last in that struggle with the popes of which the real basis was the question whether the headship of Western Christendom was to belong to the State or the Church. The noblest of them, Frederick Barbarossa (1152-1189), had all the qualities that made him the darting hero of the people: brave, handsome, able in war and in council--a liberal patron of the singers and builders, whose arts were beginning everywhere to flourish on the German soil--the champion of his country against the Papal chair--the conqueror of the warlike Normans of Southern Italy,--he stirred the hearts of the people with an enthusiasm that was in itself an education. The very manner of his death threw a legendary halo round his memory. That 32 their monarch should at last have taken the Cross in his old age, and far away in the Eastern land, when a river had to be crossed, should have plunged in on horseback before his whole army, to show the way, and perished in the attempt, seemed a fitting end for so brave a life; yet the mass of the people would not believe he was dead: in the popular imagination he became confounded with his great predecessor Charlemagne, and the legend was transferred to him, of the sleeping monarch in a hidden cave who was to start to life again in his country's utmost need.

The Crusades

But not only did the frequent expeditions of the Hohenstauffens into Italy bring the Germans into contact with the more refined culture of the Lombard cities and the southern Normans, yet wider fields were opened to them by the Crusades. It was at this period that one mighty impulse thrilled through Western Christendom, and drew men, women, and children even, nobles and peasants alike, to the service of the Cross. It was no wonder that men's hearts were attracted to a service which in this new form touched the springs of loyal allegiance to the invisible Lord, and of reverent compassion for His earthly sufferings, and also of worldly ambition and love of adventure, and opened to the soldier a means of securing as high a place in the heavenly kingdom by his own craft of fighting, as the monk could gain by prayer and mortification. And so for the next two hundred years there was a constant stream of Crusaders going to and returning from the East, and rendering the intercourse between the East and West almost as close as that between Europe and America in our own day. If these expeditions wrought much harm and misery by their 33 terrible drain on the strongest part of the population, by the wild habits and unknown forms of disease (such as the Oriental leprosy and plague) which were brought home by returning bands of pilgrims, they also wrought much good. Many joined them from a true impulse of devotion, and came back trained and tempered knights and warriors who had learned letters and refinement from the Normans and Provençals; the priest and scholar brought back new ideas and new manuscripts from Greece; the merchant discovered new channels for commerce, and carried home new fruits and luxuries to his native fields and city. Germany, however, was less affected by the universal enthusiasm than the other European nations: it was longer before the fire was kindled in the slow hearts of the people: the struggles with the popes made enterprises patronised by them less popular; and there were never wanting men who looked on them with a disenchanted eye. "If it were of a truth so grievous to our Lord Christ," says one of the Minne-singers, "that the Saracens should rule over the spot of His entombment, could not He alone humble the power of the heathen nation, and would He need our hands to help Him?" An old monkish chronicle of Wurzburg begins its narration of the second crusade under the Emperor Conrad III., by declaring that in the year 1147, "there came into the country false prophets, sons of Belial, sworn servants of Antichrist, who by their empty words seduced Christians, and by their vain preaching impelled all kinds of men to go forth to deliver Jerusalem from the Saracens." It goes on to describe the mixed multitude that was 34 gathered together for this purpose, and the very mixed motives that actuated them. "The one had this, the other that object. For many were curious after new things, and went forth to behold a strange land; others were constrained by poverty and the meanness of their circumstances at home, and these were ready to fight not only with the foes of the Cross of Christ, but with any good friends to Christendom, if thereby they might but get rid of this their poverty. Others again were burdened with debt, or hoped secretly to escape from the services they owed to their lord, or they feared the merited punishment of their misdeeds; all these simulated great zeal for God, but they were zealous only to throw down the heavy load of their own troubles. Scarce a few could be found who had not bowed the knee to Baal; who were guided by a pious and meritorious intention, and were so inflamed by the love of the Divine Majesty, that they were ready to shed their blood for the Most Holy Place. But we will leave this matter to Him who can read all hearts, only adding, that God best knoweth who are His." Similar judgments are expressed by many other writers throughout the twelfth century; and even where the poet or chronicler is filled with enthusiasm for the great idea embodied in these enterprises, we find a curiously frank and shrewd exposure of the defects in their execution. This mood of mind, a sort of slow practical good sense and perception of actual facts, may explain the circumstance noticed by many of their contemporaries, that the Germans were the last to join and the first to discontinue the Crusades. Still there is also a great capacity for enthusiasm in 35 the German people, and they by no means stood apart altogether from what constituted the great life of Europe in those days. Four of their emperors took the Cross, and were followed to the East by immense armies, and many knights joined in other expeditions.

The immediate fruit of this participation in the common life of Christendom was the rapid development of the institution of chivalry, and of a national literature--the first great outburst of German poetry and song. It came almost suddenly. We seem to pass at a bound from an age when literature was almost exclusively Latin and in the hands of the clergy, to one when it is German and chiefly in the hands of the knightly order. A few compositions indeed remain from the early part of the twelfth century which mark the period of transition; for though in language and subject they approach the new school, they are still the work of the clerical class. Such in religious poetry are the "Life of Jesus," by a nun who died in 1127, the version of the Pentateuch, and in secular poetry the Lays of Roland and of Alexander, &c., written by priests. But very soon a whole large55More than two hundred are known to us still by name. class of lyrical poets sprang up who are known to us as the Minne-singers; their works are in German, and show a wonderful mastery over the language. Instead of the imperfect rhymes and halting metre of the previous age, we have long poems in intricate metre and crowded with rhymes, which occur often in the middle as well as at the end of each line. It became the fashion to compose if possible, at least to learn and sing these poems. They flew over the country on the wings of the tunes attached to them; 36 wandering knights and grooms taught them to each other; they were sung at village-wakes, and at courts and tournaments; and ladies had collections of them written on slips of parchment and tied together with bright-coloured ribbons. The subjects of this new poetry were, except in some rare cases, limited in range. It concerned itself almost entirely with ladies' love, with feats of arms, and with that contrast between the bright and dark side of human life which was so strongly felt throughout the mediaeval times, and never more so than at this period. It was, unlike that which had preceded it, an age when there was great enjoyment of life,--delight in adventure, in social intercourse, and knightly pastimes; delight in natural beauty, such as the glow of summer and the song of birds, in the beauty of women, of costume, of verse, of stately buildings. There is a strain of almost childlike gaiety to be heard in most of these old poets. But it was also a time when life was peculiarly uncertain; when long partings from home and friends, strange vicissitudes of fortune, or death, might overtake at any moment those in highest place; while the Christian faith had awakened in the thoughtful Teutonic race that sense of the incompleteness and inadequacy of all finite beauty, of remorse for sin, of mysterious awe in face of the eternal destinies of man, which once roused could never be wholly laid to sleep again. The very changes of the seasons came with a sharper contrast to those men in their rude uncomfortable abodes than we in our ceiled and glazed houses can well imagine. Winter was a time of darkness, discomfort, and isolation; spring brought life and hope, and was welcomed all over 37 the country by symbolic festivals at which the prince and princess of May and their followers encountered and overcame the representative of savage Winter. Summer brought the happy out-of-doors toil to the husbandman; the tournament, or the real combat, or the wandering life to lady, and knight, and squire. No wonder then, that in the poetry of these days, the alternation of joy and sorrow, "Freud und Leid," meets us in every form; in the happiness of greeting and the pain of parting; in the gloom of winter and the joyousness of the May-time; in the praise of pleasure, and in meditations on penitence and death.

German Sequences

In the Church, too, the voice of native song now made itself heard. The German Sequences, "Leisen," or "Leiche,"66The origin of this term is uncertain, but it is thought to have denoted at first a certain dance measure. It is often applied to very long poems of somewhat irregular structure. as they were also called, became much more common, and at the highest festivals were sung even at the service of the mass itself. One for Easter, which we meet with in many various forms, and another for Whitsuntide, were thus used, and have descended to the present day as the first verses of two of Luther's best-known hymns:--

Christus ist erstanden

|

Or in other forms--

|

Or,

|

And for Whitsuntide, "here singeth the whole Church," as an old manuscript says,--

Nu biten wir den heiligen geist

|

These are attributed to Spervogel, a writer of the twelfth century, of whom we only know that he was a priest, of a burgher family, and a favourite sacred poet of that time. He composed many short didactic poems, almost epigrammatic in brevity and condensed thought, which were the beginning of a class of religious poetry that was much loved and practised in the next two or three centuries.

Another "Leich" or "Sequence" of his, which became extremely popular, is

THE PRAISE OF GOD.

i

Wurze des waldes

|

Another of his poems is called

HEAVEN AND HELL.

i

Er ist gewaltic unde Starc

|

The Minne-Singers

Several of the great Latin hymns were also translated into German at this time; and that these hymns and sequences were used in church is proved by a passage in a Life of St. Bernard by a contemporary and disciple, in which it is expressly mentioned that in the cathedral at Cologne the people broke out into hymns of praise in the German tongue at every miracle wrought by the saint; and the writer regrets that when they left the German soil this custom ceased, as the nations who spoke the Romanic languages did not possess native hymns after the manner of the others. Still undoubtedly their use in church was very restricted, and was always regarded with suspicion by the more papal of the clergy; but there were many other occasions in life on which they were employed: they seem to have been commonly sung at the saints' festivals and special services which were frequently held outside the church, and on pilgrimages. So St. Francis, in an address to his monks in the year 1221, says: "There is a certain country called Germany, wherein dwell Christians, and of a truth very pious ones, who as you know often come as pilgrims into our land, with their long staves and great boots; and amid the most sultry heat and bathed in sweat, yet visit all the thresholds of the holy shrines, and sing hymns of praise to God and all His saints." 41

It may give us some idea of the quantity of poetry written from this time onwards, that the great collection by M. Wackernagel of religious poetry prior to the Reformation, contains nearly 1500 pieces, and the names of 85 different poets, while many of the poems are anonymous, and much no doubt has perished. Among the names still left a large number are secular, others are those of monks and priests, and the vanity of the world forms not unnaturally their frequent theme. Here is a graceful little poem of this kind by a monk of the thirteenth century, entitled

THE BEAUTY OF THIS WORLD.

Diu rose ist die schoeneste under alle

|

But in the list we also find the greatest of the knightly Minne-singers, Hartmann von der Aue, Reinmar von Hagenau, Gottfried von Strasburg, Wolfram von Eschenbach, and the noble singer Walther von der Vogelweide.

Hartmann "of the Meadow," as he calls himself 42 has left us several crusaders' songs, and among them the following:--

CRUSADER'S HYMN.

Min fröede wart nie sorgelos

|

Another crusading song, which was very widely used on pilgrimages in these days, was sung to a melody which has been preserved to the present 43 time, by its connexion with one of Luther's hymns;77That on the Ten Commandments. it is this:--

PILGRIM'S SONG.

In Gotes namen faren wir

|

Another crusader and Minne-singer of those days, Sir Reinmar of Hagenau, gives us a glimpse of the struggle that must have gone on in many minds between the love of pleasure and the self-control that befitted a soldier of the Cross, a struggle of which we 44 may still use his own words, "full many another feels it too:--"

UNRULY THOUGHTS.

Des tages do ich daz kriuze nam

|

A little anonymous poem of the same date, the last verse of which appears, from the metre, to be incomplete, surprises us by what seems to us the modern tone of its tender and passionate

LAMENT.

O wê des smerzen

|

Walter von der Vogelweide

But among all these singers, Walter von der Vogelweide (of the Birds' nests or the aviary) may be singled out as their highest type. He was the darling of his own times, and is constantly referred to by other poets as "their master in the lovely art of words and tones," "the sweetest of all nightingales," &c. It is not known what part of Germany was his birthplace, but he travelled all over it in the course of his life; he was a welcome guest at its courts, especially those of Thuringia and Austria, and he was a crusader. His poems give us the picture of a life such as we can well understand in these days, however different the circumstances may be,--a life full of travel, and of interest in questions of politics and religion, and even of literature. For the frequent reference to each other's works by these Minne-singers, with criticism or with praise, shows that those days too had their literary world. A large number of his poems are like those of the other Minne-singers, filled with praises of his lady, and of the May-time,--graceful, tender, often quaint and naive lyrics. So one begins:--

So die bluomen uz dem grase dringent

|

And again--

MAY MIRACLES.

* * * *

Muget in schowen waz dem meien

|

But others treat of higher and more serious themes, and show us a man deeply engaged in the political and religious life of his day. He was a warm lover of his country, but he does not hesitate to rebuke and satirize his countrymen, whether clergy or laity, for their faults and shortcomings. In the great struggle between the Pope and the Emperor, he is heart and soul on the national side, and writes such stern reproofs and bitter epigrams on the Head of the Church, as startle us from one of its sons. But he is an earnest Christian, sometimes lamenting his own sins with simple penitence, sometimes expressing a strong and manly faith. He preaches the Crusade, and so heartily that he refuses the meed of a poet's praises to the archangels themselves, if they come not to the succour of Christendom.

We give first one of his famous patriotic songs, then three of his religious poems, and then a crusader's hymn.

THE PRAISE OF GERMANY.

Ir sult sprechen willekomen

|

A MORNING PRAYER.

Mit saelden müeze ich hiute ûf steh

|

EQUALITY BEFORE GOD.

Swer âne vorhte, herre Got

|

REPENTANCE.

Vil wol gelobter Got wie selten ich dich prîse

|

IN THE HOLY LAND.

Nu alrest leb ich mir werde.

|

The Minne-songs, which form a purely lyrical poetry, were soon followed by poems of the narrative and didactic class. Early in this same thirteenth century the Nibelungen-Lied received its present 54 shape; and the old legends, some like this taken from the heathen times, others of purely Christian origin, became the favourite subjects of the poets. The stories of Tristram, Percival, and the quest of the Holy Grail--knightly romances and histories of saints that were half mystical and symbolical, half legendary--must have filled the imaginations of youths and ladies in those days as novels do in ours. Most of these stories were connected with that circle of legends of which King Arthur and his Round Table form the centre, and were thus derived from a foreign, generally from a French or Provençal source, but their treatment was entirely German. It soon betrays two opposite tendencies, one of which takes up the external side of these romances, that of love of adventure and worldly success; while the other brings into relief their religious element and the development of character, and anticipates in the latter respect somewhat of the characteristics of the modern novel. Of these schools the representative types are Gottfried von Strasburg and Wolfram von Eschenbach. The former chose for the subject of his longest poem the story of Tristram and Iseult, and makes it the vehicle of depicting the knightly life of his own times on its most stirring and fascinating side. The latter selects the quest of the Holy Grail by Sir Percival, and embodies in his poem those grave and high conceptions of knightly duty and religious faith, which characterise the more serious thought of his day. Wolfram von Eschenbach was a Bavarian by birth, of ancient and noble family, but being a younger son, he possessed but little worldly wealth, and seems to have led a wandering life, 55 welcome as knight and poet alike at the German courts and castles. From the frequent allusions in his principal poem to the court of Thuringia, he no doubt formed one of the band of knights, poets, and adventurers, who gathered round the Landgrave Hermann of Thuringia, and made that little court at once brilliant and disturbed. Wolfram's lifetime coincided with the brightest period of the German Empire under the Hohenstauffens, for he was born under Frederick Barbarossa, and died under Frederick II. German chivalry was then at its highest point, and religious fervour was kindled to enthusiasm by the Crusades; thus it is but natural that these should form the moving springs of his romance.

Sir Percival

It opens with the history of Gamuret, the father of Percival, a younger son of the noble house of Anjou, a knight of the adventure-loving order, who can never enjoy life but in stirring action. He takes service at one time under the Caliph of Bagdad, and wins the hand of a Saracen princess. But he soon leaves her to seek new conflicts, and after his departure she bears him a son, who grows up a heathen, but a very brave and noble knight. At last in Spain he obtains, as victor in a tournament, the hand of the queen and a large territory, and for a time lives happily with his wife; but hearing that his former sovereign is in need of his services, he sets out for the East, and is slain by the way. The queen almost dies of grief for his death, but lives at last for the sake of her little son Percival. Fearing, however, lest he should inherit his father's spirit and meet with his father's fate, she retires with him into a deep forest, where she brings him up in perfect seclusion, and forbids the few faithful 56 attendants who had followed her, ever to name chivalry or knighthood in his presence:--

But her precautions are unavailing. One day three shining knights come riding through the green forest. The boy thinks they must be gods, they are so bright, and kneels to them. They tell him they are knights, show him their weapons, and, when he wants to know how he may become like them, tell him to seek King Arthur's court. Now nothing can detain the boy, his mother finds her tears are useless, and gives permission for his departure; but hoping to drive him back to her through disgust with the world, she sends him forth in a fool's dress, bidding him to wear it for her sake, to honour old men, and to prize a woman's kiss and her ring. So he sets out, and meets with various adventures to which his simplicity and unknightly dress give a half-comic air; he makes his way, however, by dint of courage and straightforwardness, and comes at last to King Arthur's court. Here he undertakes a combat with a knight in red armour, Ither, and slays him; but though Arthur and Guinevere receive him kindly, touched by his beauty, his courage, and his simplicity, he finds himself an object of derision to the other knights and ladies, and makes his escape carrying 58 with him the armour and horse of the Red Knight. After a while he reaches the castle of a grey-haired noble knight, and, remembering his mother's instructions to ask the counsel of old men, he goes up to the knight and requests from him shelter and advice. Here he remains for some time, and speedily becomes proficient in knightly exercises and demeanour, assisted partly by a flying fancy that he feels for his host's fair daughter, Liasse. But he knows that he has not yet earned the right to a lady's love, and moreover the longing for action is upon him, and so once more he departs:--

In time he meets with a most beautiful princess, Konduiramir, who is besieged by cruel foes; he rescues her, falls deeply in love with her, and is at last rewarded by her hand and crown, and lives for a time happily with her. The land flourishes under his wise and mild sway, and all seems going well, till he remembers how long it is since he has had news of his mother, and sets forth to find her once more.