Contents

| « Prev | CHAPTER VII | Next » |

CHAPTER VII.

CAMPAIGN AGAINST THE VAUDOIS OF MÉRINDOL AND CABRIÈRES, AND LAST DAYS OF FRANCIS THE FIRST.

| Campaign against the Vaudois of Mérindol and Cabrières, and Last Days of Francis I. | 230 | |

| The Vaudois of the Durance | 230 | |

| Their Industry and Thrift | 230 | |

| Embassy to German and Swiss Reformers | 232 | |

| Translation of the Bible by Olivetanus | 233 | |

| Preliminary Persecutions | 234 | |

| The Parliament of Aix | 235 | |

| The Atrocious "Arrêt de Mérindol" (Nov. 18, 1540) | 236 | |

| Condemned by Public Opinion | 237 | |

| Preparations to carry it into Effect | 237 | |

| President Chassanée and the Mice of Autun | 238 | |

| The King instructs Du Bellay to investigate | 239 | |

| A Favorable Report | 240 | |

| Francis's Letter of Pardon | 241 | |

| Parliament's Continued Severity | 241 | |

| The Vaudois publish a Confession | 242 | |

| Intercession of the Protestant Princes of Germany | 242 | |

| The new President of Parliament | 243 | |

| Sanguinary Royal Order, fraudulently obtained (Jan. 1, 1545) | 244 | |

| Expedition stealthily organized | 245 | |

| Villages burned—their Inhabitants murdered | 246 | |

| Destruction of Mérindol | 247 | |

| Treacherous Capture of Cabrières | 248 | |

| Women burned and Men butchered | 248 | |

| Twenty-two Towns and Villages destroyed | 249 | |

| A subsequent Investigation | 251 | |

| "The Fourteen of Meaux" | 253 | |

| Wider Diffusion of the Reformed Doctrines | 256 | |

| The Printer Jean Chapot before Parliament | 256 | |

The Vaudois of Provence.

Their industry and thrift.

Vaudois settlements even in the Comtât Venaissin.

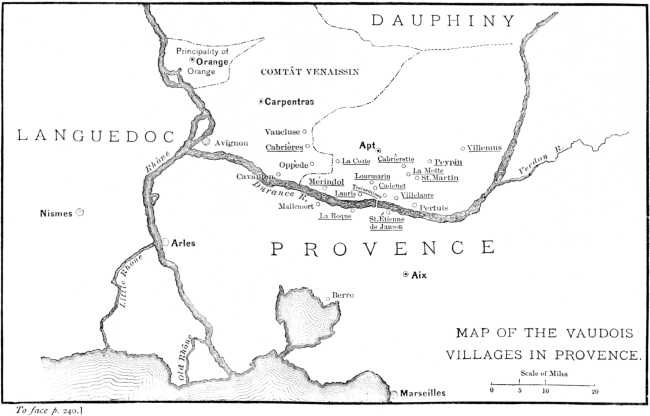

That part of Provence, the ancient Roman Provincia, which skirts the northern bank of the Durance, formerly contained, at a distance of between twenty and fifty miles above the confluence of the river with the Rhône near Avignon, more than a score of small towns and villages inhabited by peasants of Waldensian origin. The entire district had been desolated by war about a couple of centuries before the time of which we are now treating. Extensive tracts of land were nearly depopulated, and the few remaining tillers of the soil obtained a precarious subsistence, at the mercy of banditti that infested the mountains and forests, and plundered unfortunate travellers. Under these circumstances, the landed gentry, impoverished through the loss of the greater part of their revenues, gladly welcomed the advent of new-comers, who were induced to cross the Alps from the valleys of Piedmont and occupy the abandoned farms.449449 This was true particularly of the wealthy noble family to whom belonged the fief of Cental, perhaps at a somewhat later date. Among the Waldensian villages owned by it were those of La Motte d'Aigues, St. Martin, Lourmarin, Peypin, and others in the same vicinity. Bouche, Histoire de Provence, i. 610. By the industrious culture of the Vaudois, or Waldenses, the face of the country was soon transformed. Villages sprang up where there had scarcely been a single house. Brigandage disappeared. Grain, wine, olives, and almonds were obtained in abundance from what had been a barren waste. On lands231 less favorable for cultivation numerous flocks and herds pastured.450450 Crespin, Actiones et Monimenta (Geneva, 1560), fols. 88, 90, 100. A tract formerly returning the scanty income of four crowns a year now contained a thriving village of eighty substantial houses, and brought its owners nearly a hundredfold the former rental.451451 Ibid., ubi supra, fol. 100; Garnier, Histoire de France, xxvi. 27. On one occasion at least, discouraged by the annoyance to which their religious opinions subjected them, a part of the Vaudois sought refuge in their ancient homes, on the Italian side of the mountains. But their services were too valuable to be dispensed with, and they soon returned to Provence, in answer to the urgent summons of their Roman Catholic landlords.452452 Leber, Collection de pièces rel. à l'hist. de France, xvii. 550. In fact, a very striking proof both of their industry and of their success is furnished by the circumstance that Cabrières, one of the largest Vaudois villages, was situated within the bounds of the Comtât Venaissin, governed, about the time of their arrival, by the Pope in person, and subsequently, as we have seen, by a papal legate residing in Avignon.453453 The Comtât Venaissin was not reincorporated in the French monarchy until 1663. Louis XIV., in revenge for the insult offered him when, on the twentieth of August of the preceding year, his ambassador to the Holy See was shot at by the pontifical troops, and some of his suite killed and wounded, ordered the Parliament of Aix to re-examine the title by which the Pope held Avignon and the Comtât. The parliament cited the pontiff, and, when he failed to appear, loyally declared his title unsound, and, under the lead of their first president (another Meynier, Baron d'Oppède), proceeded at once to execute sentence by force of arms, and oust the surprised vice-legate. No resistance was attempted. Meynier was the first to render homage to the king for his barony; and the people of Avignon, according to the admission of the devout historian of Provence, celebrated their independence of the Pope and reunion to France by Te Deums and a thousand cries of joy and thanksgiving to Almighty God. Bouche, Histoire de Provence, ii. (Add.) 1068-1071.

They send delegates to the Swiss and German reformers.

The news of an attempted reformation of the church in Switzerland and Germany awakened a lively interest in this community of simple-minded Christians. At length a convocation of their ministers454454 "Ministri, quos Barbas eorum idiomate id est, avunculos, vocabant." Crespin, fol. 88. at Mérindol, in 1530, determined to232 send two of their number to compare the tenets they had long held with those of the reformers, and to obtain, if possible, additional light upon some points of doctrine and of practice respecting which they entertained doubt. The delegates were George Morel, of Freissinières, and Pierre Masson, of Burgundy. They visited Œcolampadius at Basle, Bucer and Capito at Strasbourg, Farel at Neufchâtel, and Haller at Berne. From the first-named they received the most important aid, in the way of suggestions respecting the errors455455 The Histoire ecclésiastique, i. 22, while admitting that the Vaudois "had never adhered to papal superstition," asserts that "par longue succession de temps, la pureté de la doctrine s'estoit grandement abastardie." From the letter of Morel and Masson to Œcolampadius, it appears that, in consequence of their subject condition, they had formed no church organization. Their Barbes, who were carefully selected and ordained only after long probation, could not marry. They were sent out two by two, the younger owing implicit obedience to the elder. Every part of the extensive territory over which their communities were scattered was visited at least once a year. Pastors, unless aged, remained no longer than three years in one place. While supported in part by the laity, they were compelled to engage in manual labor to such an extent as to interfere much with their spiritual office and preclude the study that was desirable. The most objectionable feature in their practice was that they did not themselves administer the Lord's Supper, but, while recommending to their flock to discard the superstitions environing the mass, enjoined upon them the reception of the eucharist at the hands of those whom they themselves regarded as the "members of Antichrist." Œcolampadius, while approving their confession of faith and the chief points of their polity, strenuously exhorted them to renounce all hypocritical conformity with the Roman Church, induced by fear of persecution, and strongly urged them to put an end to the celibacy and itinerancy of their clergy, and to discontinue the "sisterhoods" that had arisen among them. The important letters of the Waldensee delegates and of Œcolampadius are printed in Gerdes., Hist. Evang. Renov., ii. 402-418. An interesting account of the mission is given by Hagenbach, Johann Oekolampad und Oswald Myconius, 150, 151. into which the isolated position they had long occupied had insensibly led them. Grateful for the kindness manifested to them, and delighted with what they had witnessed of the progress of the faith they had received from their fathers, the two envoys started on their return. But Morel alone succeeded in reaching Provence; his companion was arrested at Dijon and condemned to death. Upon the233 report of Morel, however, the Waldenses at once began to investigate the new questions that had been raised, and, in their eagerness to purify their church, sent word to their brethren in Apulia and Calabria, inviting them to a conference respecting the interests of religion.456456 Crespin, fol. 89; Hist. ecclés., i. 22; Herminjard, iii. 66.

They furnish means for publishing the Scriptures.

A few years later (1535) the Waldenses by their liberal contributions furnished the means necessary for publishing the translation of the Holy Scriptures made by Pierre Robert Olivetanus, and corrected by Calvin, which, unless exception be made in favor of the translation by Lefèvre d'Étaples, is entitled to rank as the earliest French Protestant Bible.457457 Printed at Neufchâtel, by the famous Pierre de Wringle, dit Pirot Picard; completed, according to the colophon, June 4, 1535. The Waldenses having determined upon its publication at the Synod of Angrogna, in 1532, collected the sum, enormous for them, of 500 (others say 1,500) gold crowns. Adam (Antoine Saunier) to Farel, Nov. 5, 1532, Herminjard, ii. 452. Monastier, Hist. de l'église vaudoise, i. 212. The part taken by the Waldenses in this publication is attested beyond dispute by ten lines of rather indifferent poetry, in the form of an address to the reader, at the close of the volume: It was a noble undertaking, by which the poor and humble inhabitants of Provence, Piedmont, and Calabria conferred on France a signal benefit, scarcely appreciated in its full extent even by those who pride themselves upon their acquaintance with the rich literature of that country. For, while Olivetanus in his admirable version laid the founda234tion upon which all the later and more accurate translations have been reared, by the excellence of his modes of expression he exerted an influence upon the French language perhaps not inferior to that of Calvin or Montaigne.458458 "D'un commun accord," says an able critic, "on a mis Calvin à la tête de tous nos écrivains en prose; personne n'a songé à méconnaître les obligations que lui a notre langue. D'où vient qu'on a été moins juste envers Robert Olivetan, tandis qu'à y regarder de près, il y a tout lieu de croire que sa part a été au moins égale à celle de Calvin dans la réformation de la langue? L'Institution de Calvin a eu un très-grand nombre de lecteurs; mais il n'est pas probable qu'elle ait été lue et relue comme la Bible d'Olivetan." Le Semeur, iv. (1835), 167. By successive revisions this Bible became that of Martin, of Osterwald, etc.

Preliminary persecutions.

Intelligence of the new activity manifested by the Waldenses reaching the ears of their enemies, among whom the Archbishop of Aix was prominent, stirred them up to more virulent hostility. The accusation was subsequently made by unfriendly writers, in order to furnish some slight justification for the atrocities of the massacre, that the Waldenses, emboldened by the encouragement of the reformers, began to show a disposition to offer forcible resistance to the arbitrary arrests ordered by the civil and religious authorities of Aix. But the assertion, which is unsupported by evidence, contradicts the well-known disposition and practice of a patient people, more prone to submit to oppression than to take up arms even in defence of a righteous cause.459459 Sleidan (Fr. trans. of Courrayer), ii. 251, who remarks of this charge of rebellion, "C'est l'accusation qu'on intente maintenant le plus communément, et qui a quelque chose de plus odieux que véritable."

The Dominican De Roma foremost in the work.

Iniquitous order of the Parliament of Aix.

For a time the persecution was individual, and therefore limited. But in the aggregate the number of victims was by no means inconsiderable, and the flames burned many a steadfast Waldensee.460460 Professor Jean Montaigne, writing from Avignon, as early as May 6, 1533, said: "Valdenses, qui Lutheri sectam jamdiu sequuntur istic male tractantur. Plures jam vivi combusti fuerunt, et quotidie capiuntur aliqui; sunt enim, ut fertur, illius sectæ plus quam sex millia hominum. Impingitur eis quod non credant purgatorium esse, quod non orent Sanctos, imo dicant non esse orandos, teneant decimas non esse solvendas presbyteris, et alia quædam id genus. Propter quæ sola vivos comburunt, bona publicant." Basle MS., Herminjard, iii. 45. The Dominican De Roma enjoyed an unenviable notoriety for his ferocity in deal235ing with the "heretics," whose feet he was in the habit of plunging in boots full of melted fat and boiling over a slow fire. The device did, indeed, seem to the king, when he heard of it, less ingenious than cruel, and De Roma found it necessary to avoid arrest by a hasty flight to Avignon, where, upon papal soil, as foul a sink of iniquity existed as anywhere within the bounds of Christendom.461461 Crespin and the Hist. ecclés. place De Roma's exploits before, De Thou relates them after the massacre. As to the surpassing and shameless immorality of the ecclesiastics of Avignon, it is quite sufficient to refer to Crespin, ubi supra, fol. 97, etc., and to the autobiography of François Lambert, who is a good witness, as he had himself been an inmate of a monastery in that city. But other agents, scarcely more merciful than De Roma, prosecuted the work. Some of the Waldenses were put to death, others were branded upon the forehead. Even the ordinary rights of the accused were denied them; for, in order to leave no room for justice, the Parliament of Aix had framed an iniquitous order, prohibiting all clerks and notaries from either furnishing the accused copies of legal instruments, or receiving at their hands any petition or paper whatsoever.462462 Crespin, fol. 103, b. Such were the measures by which the newly-created Parliament of Provence signalized its zeal for the faith, and attested its worthiness to be a sovereign court of the kingdom.463463 The Parliament of Provence, with its seat at Aix, was instituted in 1501, and was consequently posterior in date and inferior in dignity to the parliaments of Paris, Toulouse, Grenoble, Bordeaux, Dijon, and Rouen. From its severe sentences, however, appeals had once and again been taken by the Waldenses to Francis, who had granted them his royal pardon on condition of their abjuration of their errors within six months.464464 By royal letters of July 16, 1535, and May 31, 1536. Histoire ecclés., i. 23.

Inhabitants of Mérindol cited.

The slow methods heretofore pursued having proved abortive, in 1540 the parliament summoned to its bar, as suspected of heresy, fifteen or twenty465465 There is even greater discrepancy than usual between the different authorities respecting the number of Waldenses cited and subsequently condemned to the stake. Crespin, fol. 90, gives the names of ten, the royal letters of 1549 state the number as fourteen or fifteen, the Histoire ecclésiastique as fifteen or sixteen. M. Nicolaï (Leber, Coll. de pièces rel. à l'hist. de France, viii. 552) raises it to nineteen, which seems to be correct. of the inhabitants of the village of Mérindol. On the appointed day the accused made their way to Aix, but, on stopping to236 obtain legal advice of a lawyer more candid than others to whom they had first applied, and who had declined to give counsel to reputed Lutherans, they were warned by no means to appear, as their death was already resolved upon. They acted on the friendly injunction, and fled while it was still time.

The atrocious Arrêt de Mérindol, Nov. 18, 1540.

Finding itself balked for the time of its expected prey, the parliament resolved to avenge the slight put upon its authority, by compassing the ruin of a larger number of victims. On the eighteenth of November, 1540, the order was given which has since become infamous under the designation of the "Arrêt de Mérindol." The persons who had failed to obey the summons were sentenced to be burned alive, as heretics and guilty of treason against God and the King. If not apprehended in person, they were to be burned in effigy, their wives and children proscribed, and their possessions confiscated. As if this were not enough to satisfy the most inordinate greed of vengeance, parliament ordered that all the houses of Mérindol be burned and razed to the ground, and the trees cut down for a distance of two hundred paces on every side, in order that the spot which had been the receptacle of heresy might be forever uninhabited! Finally, with an affectation which would seem puerile were it not the conclusion of so sanguinary a document, the owners of lands were forbidden to lease any part of Mérindol to a tenant bearing the same name, or belonging to the same family, as the miscreants against whom the decree was fulminated.466466 Histoire ecclés., i. 23; Crespin, Actiones et Monimenta, fol. 90; De Thou, i. 536; Nicolaï, ubi supra; Recueil des anc. lois françaises, xii. 698. See the arrêt in Bouche, Hist. de Provence, ubi supra. The last-mentioned author, while admitting the proceedings of the Parliament of Aix to be apparently "somewhat too violent," excuses them on the ground that the Waldenses deserved this punishment, "non tant par leurs insolences et impiétez cy-devant commises, mais pour leur obstination à ne vouloir changer de religion;" and cites, in exculpation of the parliament, the "bloody order of Gastaldo," in consequence of which, in 1655, fire, sword, and rapine were carried into the peaceful valley of Luserna (ibid., 615, 623)! The massacre of the unhappy Italian Waldenses thus becomes a capital vindication of the barbarities inflicted a century before upon their French brethren.237

It is condemned by public opinion.

A more atrocious sentence was, perhaps, never rendered by a court of justice than the Arrêt de Mérindol, which condemned the accused without a hearing, confounded the innocent with the guilty, and consigned the entire population of a peaceful village, by a single stroke of the pen, to a cruel death, or a scarcely less terrible exile. For ten righteous persons God would have spared guilty Sodom; but neither the virtues of the inoffensive inhabitants, nor the presence of many Roman Catholics among them, could insure the safety of the ill-fated Mérindol at the hands of merciless judges.467467 See the remark of M. Nicolaï (Leber, Coll. de pièces rel. à l'hist. de France, viii. 556). The publication of the Arrêt occasioned, even within the bounds of the province, the most severe animadversion; nor were there wanting men of learning and high social position, who, while commenting freely upon the scandalous morals of the clergy, expressed their conviction that the public welfare would be promoted rather by restraining and reforming the profligacy of the ecclesiastics, than by issuing bloody edicts against the most exemplary part of the community.468468 Crespin (fols. 91-94) gives an interesting report of some discussions of the kind. It may be remarked that the Archbishop of Aix, who was the prime mover in the persecution, had exposed himself to unusual censure on the score of irregularity of life.

Preparations to carry it into effect.

Meantime, however, the archbishops of Arles and of Aix urged the prompt execution of the sentence, and the convocations of clergy offered to defray the expense of the levy of troops needed to carry it into effect. The Archbishop of Aix used his personal influence with Chassanée, the First President of the Parliament, who, with the more moderate judges, had only consented to the enactment as a threat which he never intended to execute.469469 The remark is ascribed to Chassanée: "itaque decretum ipsi tale fecissent, eo consilio factum potius, ut Lutheranis, quorum multitudinem augeri quotidie intelligebant, metus incuteretur, quam ut revera id efficeretur quod ipsius decreti capitibus continebatur." Crespin, ubi supra, fol. 98. And the wily238 prelate so far succeeded by his arguments, and by the assurance he gave of the protection of the Cardinal of Tournon, in case the matter should reach the king's ears, that the definite order was actually promulgated for the destruction of Mérindol. Troops were accordingly raised, and, in fact, the vanguard of a formidable army had reached a spot within three miles of the devoted village, when the command was suddenly received to retreat, the soldiers were disbanded, and the astonished Waldenses beheld the dreaded outburst of the storm strangely delayed.470470 Crespin, ubi supra, fol. 100.

It is delayed by friendly interposition.

The "mice of Autun."

The unexpected deliverance is said to have been due to the remonstrance of a friend, M. d'Allens. D'Allens had adroitly reminded the president of an amusing incident by means of which Chassanée had himself illustrated the ample protection against oppression afforded by the law, in the hands of a sagacious advocate and a righteous judge; and he had earnestly entreated his friend not to show himself less equitable in the matter of the defenceless inhabitants of Mérindol than he had been in that of the "mice of Autun."471471 The ludicrous story of the "mice of Autun," which thus obtains a historic importance, had been told by Chassanée himself. It appears that on a certain occasion the diocese of Autun was visited with the plague of an excessive multiplication of mice. Ordinary means of stopping their ravages having failed, the vicar of the bishop was requested to excommunicate them. But the ecclesiastical decree was supposed to be most effective when the regular forms of a judicial trial were duly observed. An advocate for the marauders was therefore appointed—no other than Chassanée himself; who, espousing with professional ardor the interests of his quadrupedal clients, began by insisting that a summons should be served in each parish; next, excused the non-appearance of the defendants by alleging the dangers of the journey by reason of the lying-in-wait of their enemies, the cats; and finally, appealing to the compassion of the court in behalf of a race doomed to wholesale destruction, acquitted himself so successfully of his fantastic commission, that the mice escaped the censures of the church, and their advocate gained universal applause! See Crespin, fol. 99; De Thou, i. 536, Gamier, xxvi. 29, etc. Crespin, writing at least as early as 1560, speaks of the incident as being related in Chassanée's Catalogus Gloriæ Mundi; but I have been unable to find any reference to it in that singular medley.

Francis I. instructs Du Bellay to investigate.

The delay thus gained permitted a reference of the affair to239 the king. It is said that Guillaume du Bellay is entitled to the honor of having informed Francis of the oppression of his poor subjects of Provence, and invoked the royal interposition.472472 De Thou, i. 539. However this may be, it is certain that Francis instructed Du Bellay to set on foot a thorough investigation into the history and character of the inhabitants of Mérindol, and report the results to himself. The selection could not have been more felicitous. Du Bellay was Viceroy of Piedmont, a province thrown into the hands of Francis by the fortunes of war. A man of calm and impartial spirit, his liberal principles had been fostered by intimate association with the Protestants of Germany. Only a few months earlier, in 1539, he had, in his capacity of governor, made energetic remonstrances to the Constable de Montmorency touching the wrongs sustained by the Waldenses of the valleys of Piedmont at the hands of a Count de Montmian, the constable's kinsman. He had even resorted to threats, and declared "that it appeared to him wicked and villanous, if, as was reported, the count had invaded these valleys and plundered a peaceful and unoffending race of men." Montmian had retorted by accusing Du Bellay of falsehood, and maintaining that the Waldenses had suffered no more than they deserved, on account of their rebellion against God and the king. The unexpected death of Montmian prevented the two noblemen from meeting in single combat, but a bitter enmity between the constable and Du Bellay had been the result.473473 This striking incident is not noticed in the well-known Memoirs of Du Bellay, written by his brother. The reader will agree with me in considering it one of the most creditable in Du Bellay's eventful life. Calvin relates it in two letters to Farel, published by Bonnet (Calvin's Letters, i. 162, 163-165). The reformer had had it from Du Bellay's own lips at Strasbourg, and had perused the letter in which the latter threw up his alliance with Montmian, and stigmatized the baseness of his conduct.

Du Bellay's favorable report.

The viceroy, in obedience to his instructions, despatched two agents from Turin to inquire upon the ground into the character and antecedents of the people of Mérindol. Their report, which has fortunately come down to us, constitutes a brilliant testimonial from unbiassed witnesses to240 the virtues of this simple peasantry. They set forth in simple terms the affecting story of the cruelty and merciless exactions to which the villagers had for long years been subjected. They collected the concurrent opinions of all the Roman Catholics of the vicinity respecting their industry. In two hundred years they had transformed an uncultivated and barren waste into a fertile and productive tract, to the no small profit of the noblemen whose tenants they were. They were a people distinguished for their love of peace and quiet, with firmly established customs and principles, and warmly commended for their strict adherence to truth in their words and engagements. Averse alike to debt and to litigation, they were bound to their neighbors by a tie of singular good-will and respect. Their kindness to the unfortunate and their humanity to travellers knew no bounds. One could readily distinguish them from others by their abstinence from unnecessary oaths, and their avoidance even of the very name of the devil. They never indulged in lascivious discourse themselves, and if others introduced it in their presence, they instantly withdrew from the company. It was true that they rarely entered the churches, when pleasure or business took them to the city or the fair; and, if found within the sacred enclosure, they were seen praying with faces averted from the paintings of the saints. They offered no candles, avoided the sacred relics, and paid no reverence to the crosses on the roadside. The priests testified that they were never known to purchase masses either for the living or for the dead, nor to sprinkle themselves with holy water. They neither went on pilgrimages, nor invoked the intercession of the host of heaven, nor expended the smallest sum in securing indulgences. In a thunderstorm they knelt down and prayed, instead of crossing themselves. Finally, they contributed nothing to the support of religious fraternities or to the rebuilding of churches, reserving their means for the relief of tho poor and afflicted.474474 De Thou, i. 539; Crespin, ubi supra, fols. 100, 101.—Historians have noticed the remarkable points of similarity this report presents to that made by the younger Pliny to the Emperor Trajan regarding the primitive Christians. Plinii Epistolæ, x. 96, etc.

241

Francis signs a letter of pardon.

Although the enemies of the Waldenses were not silenced, and wild stories of their rebellious acts still found willing listeners at court,475475 Calvin's Letters (Bonnet), i. 228, 229. Strange to say, even M. Nicolaï, otherwise very fair, credits one of these absurd rumors (Leber, ubi supra, xvii. 557). While the inhabitants of Mérindol entered into negotiations, it is stated that those of Cabrières, subjects of the Pope, took up arms. Twice they repulsed the vice-legate's forces, driving them back to the walls of Avignon and Cavaillon. Flushed with success, they began to preach openly, to overturn altars, and to plunder churches. The Pope, therefore, Dec., 1543, called on Count De Grignan for assistance in exterminating the rebels. But the incidents here told conflict with the undeniable facts of Cardinal Sadolet's intercession for, and peaceable relations with the inhabitants of Cabrières in 1541 and 1542; as well as with the royal letters of March 17, 1549 (1550 New Style), and the report of Du Bellay. Bouche, on the weak authority of Meynier, De la guerre civile, gives similar statements of excesses, ii. 611, 612. it was impossible to resist the favorable impression made by the viceroy's letter. Consequently, on the eighth of February, 1541, Francis signed a letter granting pardon not only to the persons who by their failure to appear before the Parliament of Aix had furnished the pretext for the proscriptive decree, but to all others, meantime commanding them to abjure their errors within the space of three months. At the same time the over-zealous judges were directed henceforth to use less severity against these subjects of his Majesty.476476 Hist. ecclés., i. 24; Crespin, fol. 101; De Thou, i. 539; Bouche, ii. 612. The last asserts that this unconditional pardon was renewed by successive royal letters, dated March 17, 1543, and June 14, 1544; but that in those of Lyons, 1542, the king had meanwhile, at Cardinal Tournon's instigation, exhorted the Archbishop and Parliament of Aix to renewed activity in proceeding against the heretics. Ibid, ii. 612-614.

Parliament issues a new summons.

The Vaudois publish a confession.

Bishop Sadolet's kindness.

Little inclined to relinquish the pursuit, however, parliament seized upon the king's command to abjure within three months, as an excuse for issuing a new summons to the Waldenses. Two deputies from Mérindol accordingly presented themselves, and offered, on the part of the inhabitants, to abandon their peculiar tenets, so soon as these should be refuted from the Holy Scriptures—the course which, as they believed, the king himself had intended that they should take. As it was no part of the plan to grant so reasonable a request, the sole reply vouchsafed was a declaration that all who242 recanted would receive the benefit of the king's pardon, but all others would be reputed guilty of heresy without further inquiry. Whereupon the Waldenses of Mérindol, in 1542, drew up a full confession of their faith, in order that the excellence of the doctrines they held might be known to all men.477477 Given in full by Crespin, ubi supra, fols. 104-110, and by Gerdes., Hist. Reform., iv. 87-99; in its brief form, as originally composed in French to be laid before the Parliament of Provence, in Bulletin de l'hist. du prot. français, viii. 508, 509. Several articles were added when it was laid before Sadolet. Crespin, fol. 110. The important document was submitted not merely to parliament, but to Cardinal Sadolet, Bishop of Carpentras. The prelate was a man of a kindly disposition, and did not hesitate, in reply to a petition of the Waldenses of Cabrières, to acknowledge the falsity of the accusations laid to their charge.478478 De Thou, i. 540; Crespin, fol. 110. Not long after, he successfully exerted his influence with the vice-legate to induce him to abandon an expedition he had organized against the last-mentioned village; while, in an interview which he purposely sought with the inhabitants, he assured them that he firmly intended, in a coming visit to Rome, to secure the reformation of some incontestable abuses.479479 Crespin, fols. 110, 111.

Intercession of the Germans.

The Mérindol confession is said to have found its way even to Paris, and to have been read to the king by Châtellain, Bishop of Maçon, and a favorite of the monarch. And it is added that, astonished at the purity of its doctrine, Francis asked, but in vain, that any erroneous teaching in it should be pointed out to him.480480 Ibid., fol. 110. It is not, indeed, impossible that the king's interest in his Waldensian subjects may have been deepened by the receipt of a respectful remonstrance against the persecutions now raging in France, drawn up by Melanchthon in the name of the Protestant princes and states of Germany.481481 May 23, 1541. Bretschneider, Corpus Reform., iv. 325-328; Gerdes., iv. (Doc). 100,101. But when the Germans intervened later in behalf of the few remnants of the dispersed Waldenses, they received a decided rebuff: "Il leur répondit assez brusquement, qu'il ne se mêloit pas de leurs affaires, et qu'ils ne devoient pas entrer non plus dans les siennes, ni s'embarrasser de ce qu'il faisoit dans ses États, et de quelle manière il jugeoit à propos de châtier ses sujets coupables." De Thou, i. 541.243

Death of President Chassanée, who is succeeded by Baron d'Oppède.

Military preparations stopped by a second royal order.

The Arrêt de Mérindol yet remained unexecuted when, Chassanée having died, he was succeeded, in the office of First President of the Parliament of Provence, by Jean Meynier, Baron d'Oppède. The latter was an impetuous and unscrupulous man. Even before his elevation to his new judicial position, Meynier had looked with envious eye upon the prosperity of Cabrières, situated but a few miles from his barony; and scarcely had he taken his place on the bench, before, at his bidding, the first notes of preparation for a great military assault upon the villages of the Durance were heard. The affrighted peasants again had recourse to the mercy of their distant sovereign. A second time Francis (on the twenty-fifth of October, 1544) interfered, evoking the case from parliament, and assuming cognizance of it until such time as he might have instituted an examination upon the spot by a "Maître de requêtes" and a theologian sent by him.482482 Hist. ecclés., i. 27, 28; Crespin, fol. 114.

Calumnious accusations.

The interruption was little relished. A fresh investigation was likely to disclose nothing more unfavorable to the Waldenses than had been elicited by the inquiries of Du Bellay, or than the report which had led Louis the Twelfth, on an earlier occasion (1501), to exclaim with an oath: "They are better Christians than we are!"483483 Vesembec, apud Perrin, History of the Old Waldenses (1712), xii. 59; Garnier, xxvi. 23. and, what was worse, the poor relations, both of the prelates and of the judges, had only a sorry prospect of enriching themselves through the confiscation of the property of the lawful owners.484484 Henry II.'s letters of March 17, 1549, summoning Meynier and his accomplices to the bar of the Parliament of Paris, state distinctly the motives of the perpetrators of the massacre, as alleged by the Waldenses in their appeal to Francis I.: "Auquel ils firent entendre, qu'ils étaient journellement travaillés et molestés par les évêques du pays et par les présidens et conseillers de notre parlement de Provence, qui avaient demandé leurs confiscations et terres pour leurs parens," etc. Hist. ecclés., ubi supra. It was time to venture something244 for the purpose of obtaining the coveted prize. Accordingly, the Parliament of Aix, at this juncture, despatched to Paris one of its official servants, with a special message to the king. He was to beg Francis to recall his previous order. He was to tell him that Mérindol and the neighboring villages had broken out into open rebellion; that fifteen thousand armed insurgents had met in a single body. They had captured towns and castles, liberated prisoners, and hindered the course of justice. They were intending to march against Marseilles, and when successful would establish a republic fashioned on the model of the Swiss cantons.485485 "Sur ce que l'on auroit fait entendre audit feu Seigneur Roi, qu'ils étaient en armes en grande assemblée, forçant villes et châteaux, eximant les prisonniers des prisons," etc. Letters Patent of Henry II., ubi supra, i. 46; also, i. 28; De Thou, i. 541. Notwithstanding the evident falsity of these assertions of Courtain, the parliament's messenger, writers of such easy consciences as Maimbourg (Hist. du calvinisme, liv. ii. 83) and Freschot (Origine, progressi e ruina del Calvinismo nella Francia, di D. Casimiro Freschot, Parma, 1693, p. 34) are not ashamed to endorse them. Freschot says: "Nello stesso tempo che mandavano à Parigi le loro proposizioni, travagliavano ad accrescere le loro forze, non che ad assicurare il proprio Stato. Per il che conseguire avendo praticato alcune intelligenze nella città di Marsiglia, s'avanzarono sin' al numero di sedici mila per impossessarsene," etc. The assertions of so ignorant a writer as Freschot shows himself to be, scarcely require refutation. See, however, Le Courrayer, following Bayle, note to Sleidan, ii. 256. The impartial Roman Catholic continuation of the Eccles. Hist. of the Abbé Fleury, xxviii. 540, gives no credit to these calumnies.

Francis, misinformed, revokes his last orders.

Thus reinforced, Cardinal Tournon found no great difficulty in exciting the animosity of a king both jealous of any infringement upon his prerogative, and credulous respecting movements tending to the encouragement of rebellion. On the first of January, 1545, Francis sent a new letter to the Parliament of Aix. He revoked his last order, enjoined the execution of the former decrees of parliament, so far as they concerned those who had failed to abjure, and commanded the governor of Provence, or his lieutenant, to employ all his forces to exterminate any found guilty of the Waldensian heresy.486486 The substance of the royal order of January 1, 1545, is given in the Letters-Patent of Henry II., dated Montereau, March 17, 1549 (1550, New Style), which constitute our best authority: "Le feu dit Seigneur permit d'exécuter les arrêts donnés contre eux, révoquant lesdites lettres d'évocation, pour le regard des récidifs non ayant abjuré, et ordonna que tous ceux qui se trouveraient chargés et coupables d'hérésie et secte Vaudoise, fussent exterminés," etc. Hist. ecclés., i. 46.245

His letter construed as authorizing a new crusade.

The new order had been skilfully drawn. The "Arrêt de Mérindol," although not alluded to by name, might naturally be understood as included under the general designation of the parliament's decrees against heretics; while the direction to employ the governor's troops against those who had not abjured could be construed as authorizing a local crusade, in which innocent and guilty were equally likely to suffer. Such were the pretexts behind which the first president and his friends prepared for a carnage which, for causelessness and atrocity, finds few parallels on the page of history.

An expedition stealthily organized.

Three months passed, and yet no attempt was made to disturb the peaceful villages on the Durance. Then the looked-for opportunity came. Count De Grignan, Governor of Provence, was summoned by the king and sent on a diplomatic mission to Germany. The civil and military administration fell into the Baron d'Oppède's hands as lieutenant. The favorable conjuncture was instantly improved. On a single day—the twelfth of April—the royal letter, hitherto kept secret, that the intended victims might receive no intimations of the impending blow, was read and judicially confirmed, and four commissioners were appointed to superintend the execution.487487 The names are preserved: they were the second president, François de la Fond; two counsellors, Honoré de Tributiis and Bernard Badet; and an advocate, Guérin, acting in the absence of the "Procureur géneral." Letters-Patent of Henry II., ubi supra; De Thou, i. 541; Hist. ecclés., i. 28. Troops were hastily levied. All men capable of bearing arms in the cities of Aix, Arles, and Marseilles were commanded, under severe penalties, to join the expedition;488488 De Thou, ubi supra; Sleidan, Hist. de la réformation (Fr. trans. of Le Courrayer), ii. 252. and some companies of veteran troops, which happened to be on their way from Piedmont to the scene of the English war, were impressed into the service by D'Oppède, in the king's name.489489 The fleet carrying these troops, consisting of twenty-five galleys, was under the joint command of Poulin, Poulain, or Polin—afterward prominent in military affairs, under the name of Baron de la Garde—and of the Chevalier d'Aulps. Bouche, ii. 601. The Baron de la Garde is made the object of a special notice by Brantôme.246

Villages burned and their inhabitants butchered.

On the thirteenth of April, the commissioners, leaving Aix, proceeded to Pertuis, on the northern bank of the Durance. Thence, following the course of the river, they reached Cadenet. Here they were joined by the Baron d'Oppède, his sons-in-law, De Pouriez and De Lauris, and a considerable force of men. A deliberation having been held, on the sixteenth, Poulain, to whom the chief command had been assigned by D'Oppède, directed his course northward, and burned Cabrièrette, Peypin, La Motte and Saint-Martin, villages built on the lands of De Cental, a Roman Catholic nobleman, at this time a minor. The wretched inhabitants, who had not until the very last moment credited the strange story of the disaster in reserve for them, hurriedly fled on the approach of the soldiery, some to the woods, others to Mérindol. Unable to defend them against a force so greatly superior in number and equipment, a part of the men are said to have left their wives, old men, and children in their forest retreat, confident that if discovered, feminine weakness and the helplessness of infancy or of extreme old age would secure better terms for them than could be hoped for in case of a brave, but ineffectual defence by unarmed men.490490 Crespin, fol. 115. Sleidan and De Thou give a similar incident as befalling fugitives from Mérindol. Garnier, alluding to the absence of any attempt at self-defence on the part of the Waldenses, pertinently remarks: "On put connoître alors la fausseté et la noirceur des bruits que l'on avoit affecté de répandre sur leurs préparatifs de guerre: pas un ne songea à se mettre en défense: des cris aigus et lamentables portés dans un moment de villages en villages, avertirent ceux qui vouloient sauver leur vie de fuir promptement du côté des montagnes." Hist. de France, xxvi. 33. It was a confidence misplaced. Unresisting, gray-headed men were despatched with the sword, while the women were reserved for the grossest outrage, or suffered the mutilation of their breasts, or, if with child, were butchered with their unborn offspring. Of all the property spared them by previous oppressors, nothing was left to sustain the miserable survivors. For weeks they wandered homeless247 and penniless in the vicinity of their once flourishing settlements; and there one might not unfrequently see the infant lying on the road-side, by the corpse of the mother dead of hunger and exposure. For even the ordinary charity of the humane had been checked by an order of D'Oppède, savagely forbidding that shelter or food be afforded to heretics, on pain of the halter.491491 So say the Letters-Patent of Henry II.: "Furent faites défenses à son de trompe tant par autorité dudit Menier, que dudit de la Fond, de non bailler à boire et manger aux Vaudois, sans savoir qui ils étaient; et ce sur peine de la corde." Hist. ecclés., i. 47; Crespin, fol. 115.

Lourmarin, Villelaure, and Treizemines were next burned on the way to Mérindol. On the opposite side of the Durance, La Rocque and St. Étienne de Janson suffered the same fate, at the hands of volunteers coming from Arles. Happily they were found deserted, the villagers having had timely notice of the approaching storm.

The destruction of Mérindol.

Early on the eighteenth of April, D'Oppède reached Mérindol, the ostensible object of the expedition. But a single person was found within its circuit, and he a young man reputed possessed of less than ordinary intellect. His captor had promised him freedom, on his pledging himself to pay two crowns for his ransom. But D'Oppède, finding no other human being upon whom to vent his rage, paid the soldier the two crowns from his own pocket, and ordered the youth to be tied to an olive-tree and shot. The touching words uttered by the simple victim, as he turned his eyes heavenward and breathed out his life, have been preserved: "Lord God, these men are snatching from me a life full of wretchedness and misery, but Thou wilt give me eternal life through Jesus Thy Son."492492 Crespin, and Hist. ecclês., ubi supra.

The village razed.

Meantime the work of persecution was thoroughly done. The houses were plundered and burned; the trees, whether intended for shade or for fruit, were cut down to the distance of two hundred paces from the place. The very site of Mérindol was levelled, and crowds of laborers industriously strove to destroy every trace of human habitation. Two hun248dred dwellings, the former abode of thrift and contentment, had disappeared from the earth, and their occupants wandered, poverty-stricken, to other regions.493493 Many, overtaken in their flight, were slain by the sword, or sent to the galleys, and about twenty-five, having taken refuge in a cavern near Mus, were stifled by a fire purposely kindled at its mouth. Sleidan, ii. 255.

Treacherous capture of Cabrières.

Leaving the desolate spot, D'Oppède next presented himself, on the nineteenth of April, before the town of Cabrières. Behind some weak entrenchments a small body of brave men had posted themselves, determined to defend the lives and honor of their wives and children to their last drop of blood. D'Oppède hesitated to order an assault until a breach had first been made by cannon. Then the Waldenses were plied with solicitations to spare needless effusion of blood by voluntary surrender. They were offered immunity of life and property, and a judicial trial. When by these promises the assailants had, on the morrow, gained the interior of the works, they found them guarded by Étienne de Marroul and an insignificant force of sixty men, supported by a courageous band of about forty women. The remainder of the population, overcome by natural terror at the strange sight of war, had taken refuge—the men in the cellars of the castle, the women and children in the church.

Men butchered and women burned.

The slender garrison left their entrenchments without arms, trusting in the good faith of their enemies. It was a vain and delusive reliance. They had to do with men who held, and carried into practice, the doctrine that no faith is to be observed with heretics. Scarcely had the Waldenses placed themselves in their power, when twenty-five or more of their number were seized, and, being dragged to a meadow near by, were butchered in cold blood, in the presence of the Baron d'Oppède. The rest were taken to Aix and Marseilles. The women were treated with even greater cruelty. Having been thrust into a barn, they were there burned alive. When a soldier, more compassionate than his comrades, opened to them a way of escape, D'Oppède ordered them to be driven back at the point of the pike. Nor were those taken within the town more fortunate. The men, drawn from their subterranean re249treats, were either killed on the spot, or bound in couples and hurried to the castle hall, where two captains stood ready to kill them as they successively arrived. It was, however, for the sacred precincts of the church that the crowning orgies of these bloody revels were reserved. The fitting actors were a motley rabble from the neighboring city of Avignon, who converted the place consecrated to the worship of the Almighty into a charnel-house, in which eight hundred bodies lay slain, without respect of age or sex.494494 Hist. ecclés., i. 29; Crespin, fol. 116; De Thou, ubi supra; Sleidan, ii. 254. The deposition of Antoine d'Alagonia, Sieur de Vaucler, a Roman Catholic who was present and took an active part in the enterprise (Bouche, ii. 616-619), is evidently framed expressly to exculpate D'Oppède and his companions, and conflicts too much with well-established facts to contribute anything to the true history of the capture of Cabrières.

In the blood of a thousand human beings D'Oppède had washed out a fancied affront received at the hands of the inhabitants of Cabrières. The private rancor of a relative induced him to visit a similar revenge on La Coste, where a fresh field was opened for the perfidy, lust, and greed of the soldiery. The peasants were promised by their feudal lord perfect security, on condition that they brought their arms into the castle and broke down four portions of their wall. Too implicit reliance was placed in a nobleman's word, and the terms were accepted. But when D'Oppède arrived, a murderous work began. The suburbs were burned, the town was taken, the citizens for the most part were butchered, the married women and girls were alike surrendered to the brutality of the soldiers.495495 De Thou, i. 543; Sleidan, ii. 255. Of the affair at La Coste, the Letters-Patent of Henry II. say: "Au lieu de La Coste y auroit eu plusieurs hommes tués, femmes et filles forcées jusques au nombre de vingt-cinq dedans une grange." Ubi supra, i. 47.

The results.

For more than seven weeks the pillage continued.496496 "Et infinis pillages étaient faits par l'espace de plus de sept semaines." Ibid, ubi supra. Twenty-two towns and villages were utterly destroyed. The soldiers, glutted with blood and rapine, were withdrawn from the scene of their infamous excesses. Most of the Waldenses who had escaped sword, famine, and exposure, grad250ually returned to the familiar sites, and established themselves anew, maintaining their ancient faith.497497 Hist. ecclés., i. 30. But multitudes had perished of hunger,498498 Letters-Patent of Henry II., ubi sup. while others, rejoicing that they had found abroad a toleration denied them at home, renounced their native land, and settled upon the territory generously conceded to them in Switzerland.499499 At Geneva the fugitives were treated with great kindness. Calvin was deputed by the Council of the Republic, in company with Farel, to raise contributions for them throughout Switzerland. Reg. of Council, May, 1545, apud Gaberel, Hist. de l'église de Genève, i. 439. Nine years later the council granted a lease of some uncultivated lands near Geneva to 700 of these Waldenses. The descendants of the former residents of Mérindol and Cabrières are to be found among the inhabitants of Peney and Jussy. Reg. of Council, May, 10, 1554, Gaberel, i. 440. In one way or another, France had become poorer by the loss of several thousands persons of its most industrious class.500500 Bouche, ii. 620, states, as the results of the investigations of Auberi, advocate for the Waldenses, that about 3,000 men, women and children were killed, 666 sent to the galleys, of whom 200 shortly died, and 900 houses burned in 24 villages of Provence.

The king led to give his approval.

The very agents in the massacre were appalled at the havoc they had made. Fearing, with reason, the punishment of their crime, if viewed in its proper light,501501 Francis I., on complaint of Madame De Cental, whose son had lost an annual revenue of 12,000 florins by the ruin of his villages, had, June 10, 1545, called upon the Parliament of Aix to send full minutes of its proceedings. Bouche, ii. 620, 621. they endeavored to veil it with the forms of a judicial proceeding. A commission was appointed to try the heretics whom the sword had spared. A part were sentenced to the galleys, others to heavy fines. A few of the tenants of M. de Cental are said to have purchased reconciliation by abjuring their faith.502502 De Thou, i. 544. But, to conceal the truth still more effectually, President De la Fond was sent to Paris. He assured Francis that the sufferers had been guilty of the basest crimes, that they had been judicially tried and found guilty, and that their punishment was really below the desert of their offences.503503 "Et sachant que la plainte en était venue jusqu'à [notre] dit feu père, auraient envoyé ledit De la Fond devers lui, lequel ... aurait obtenu lettres données à Arques, le 18me jour d'août 1545, approuvant paisiblement ladite exécution; n'ayant toutefois fait entendre à notre dit feu père la vérité du fait; mais supposé par icelles lettres que tous les habitane des villes brûlées étaient connus et jugés hérétiques et Vaudois." Letters-Patent of Henry II., ubi supra, i. 47; De Thou, i. 544. Upon these representations, the king251 was induced—it was supposed by the solicitation of Cardinal Tournon—to grant letters (at Arques, on the eighteenth of August, 1545) approving the execution of the Waldenses, but recommending to mercy all that repented and abjured.504504 Letters-Patent of Henry II., ubi supra.

An investigation subsequently ordered.

Thus did the authors of so much human suffering escape merited retribution at the hands of earthly justice during the brief remainder of the reign of Francis the First. If, as some historians have asserted, that monarch's eyes were at last opened to the enormities committed in Provence, it was too late for him to do more than enjoin on his son and successor a careful review of the entire proceedings.505505 De Thou, i. 544; Hist. ecclés., i. 30. It is worthy of notice, however, that the letters of Henry II., from which we have so often drawn, and which would naturally have alluded to this incident, are silent in regard to the supposed change of view on Francis's part. After the death of Francis an opportunity for obtaining redress seemed to offer. Cardinal Tournon and Count De Grignan were in disgrace, and their places in the royal favor were held by men who hated them heartily. The new favorites used their influence to secure the Waldenses a hearing. D'Oppède and the four commissioners were summoned to Paris. Count De Grignan himself barely escaped being put on trial—as responsible for the misdeeds of his lieutenant—by securing the advocacy of the Duke of Guise, which he purchased with the sacrifice of his domains at Grignan. For fifty days the trial of the other criminals was warmly prosecuted before the Parliament of Paris; and so ably and lucidly did Auberi present the claims of the oppressed before the crowded assembly, that a severe verdict was confidently awaited.

Meagre effect.

The public expectation, however, was doomed to disappointment. Only one of the accused, the advocate Guérin, being so252 unfortunate as to possess no great influence at court, was condemned to the gallows. D'Oppède escaped with De Grignan, through the protection of the Duke of Guise, and, like his fellow-defendants, was reinstated in office.506506 De Thou, i. 545. Care was even taken to state that Guérin was punished for a different crime—that of forging papers to clear himself from accusations of malfeasance in other official duties than those in which the Waldenses were concerned, and which came to light in consequence of a quarrel between D'Oppède and himself. Garnier, xxvi. 40; Bouche, ii. 622. The leniency with which D'Oppède was treated may be accounted for in part, perhaps, by the fact that the Pope addressed Henry II. a very pressing letter in his behalf, as "persecuted in consequence of his zeal for religion." Martin, Hist. de France, ix. 480. For the rendering of a decision so flagrantly unjust the true cause must be sought in the sanguinary character of the Parisian judges themselves, who, while they were reluctant, on the one hand, to derogate from the credit of another parliament of France, on the other, feared lest, in condemning the persecuting rage of others, they might seem to be passing sentence upon themselves for the uniform course of cruelty they had pursued in the trial of the reformers.507507 "Mais, craignant ceux d'entre les juges qui n'étaient pas moins cruels et sanguinaires en leurs cœurs que les criminels qu'ils devaient juger, qu'en les condamnant ils ne vinssent à rompre le cours des jugemens qu'euxmêmes prononçaient tous les jours en pareilles cause, et voulant aussi sauver l'honneur d'un autre parlement," etc. Hist. ecclés., i. 50.

The oppressed and persecuted of all ages have been ready, not without reason, to recognize in signal disasters befalling their enemies the retributive hand of the Almighty himself lifting for a moment the veil of futurity, to disclose a little of the misery that awaits the evil-doer in another world. But, in the present instance, it is a candid historian of different faith who does not hesitate to ascribe to a special interposition of the Deity the excruciating sufferings and death which, not long after his acquittal, overtook Baron d'Oppède, the chief actor in the mournful tragedy we have been recounting.508508 "Mais il fut saisi pen après d'une douleur si excessive dans les intestins, qu'il rendit son âme cruelle au milieu des plus affreux tourmens; Dieu prenant soin lui-même de lui imposer le châtiment auquel ses juges ne l'avoient pas condamné, et qui, pour avoir été un peu tardif, n'en fut que plus rigoureux." De Thou, i. 545. See a more detailed account of his death, and the exhortations of a pious surgeon, Lamotte, of Aries, in Crespin, fol. 117. Other instances in Hist. ecclésiastique.253

New persecution at Meaux.

The ashes of Mérindol and Cabrières were scarcely cold, before in a distant part of France the flame of persecution broke out with fresh energy.509509 The story of the martyrdom of the "Fourteen of Meaux" is told in detail by Crespin, Actiones et Monimenta, fols. 117-121, and the Hist. ecclés. des égl. réf., i. 31-33. The city of Meaux, where, under the evangelical preachers introduced by Bishop Briçonnet, the Reformation had made such auspicious progress, had never been thoroughly reduced to submission to papal authority. "The Lutherans of Meaux" had passed into a proverb. Persecuted, they retained their devotion to their new faith; compelled to observe strict secrecy, they multiplied to such a degree that their numbers could no longer be concealed. Twenty years after their destruction had been resolved upon, the necessity of a regular church organization made itself felt by the growing congregations. Some of the members had visited the church of Strasbourg, to which John Calvin had, a few years before, given an orderly system of government and worship—the model followed by many Protestant churches of subsequent formation. On their return a similar polity was established in Meaux. A simple wool-carder, Pierre Leclerc, brother of one of the first martyrs of Protestant France, was called from the humble pursuits of the artisan to the responsible post of pastor. He was no scholar in the usual acceptation of the term; he knew only his mother-tongue. But his judgment was sound, his piety fervent, his familiarity with the Holy Scriptures singularly great. So fruitful were his labors, that the handful of hearers grew into assemblies often of several hundreds, drawn to Meaux from villages five or six leagues distant.

A woman's pointed remark.

A favorite psalm.

Betrayed by their size, the conventicles came to the knowledge of the magistrates, and on the eighth of September, 1546, a descent was made upon the worshipping Christians. Sixty-two persons composed the gathering. The lieutenant and provost of the city, with their meagre suite, could easily have been set at defiance. But the announcement of arrest in the king's254 name prevented any attempt either at resistance on their part, or at rescue on that of their friends. Respecting the authority of law, the Protestants allowed themselves to be bound and led away by an insignificant detachment of officers. Only the pointed remark of one young woman to the lieutenant, as she was bound, has come down to us: "Sir, had you found me in a brothel, as you now find me in so holy and honorable a company, you would not have used me thus." As the prisoners passed through the streets of Meaux, their friends neither interfered with the ministers of justice, nor exhibited solicitude for their own safety; but accompanying them, as in a triumphal procession, loudly gave expression to their trust in God, by raising one of their favorite psalms, in Clement Marot's translation:510510 Ps. 79. I quote, with the quaint old spelling, from a Geneva edition of 1638, in my possession, which preserves unchanged the original words and the grand music with which the words were so intimately associated.

Ils ont pollu, Seigneur, par leur outrage,

Ton temple sainct, Jerusalem destruite,

Si qu'en monceaux de pierres, l'on reduite.

It was neither the first time, nor was it destined to be by any means the last, that those rugged, but nervous lines thrilled the souls of the persecuted Huguenots of France as with the sound of a trumpet, and braced them to the patient endurance of suffering or to the performance of deeds of valor.

The "Fourteen of Meaux."

Dragged with excessive and unnecessary violence to Paris, the prisoners were put on trial, and, within a single month, sentence was passed on them. The crime of having celebrated the Lord's Supper was almost inexpiable. Fourteen men, with Leclerc their minister, and Étienne Mangin, in whose house their worship had been held, were condemned to torture and the stake; others to whipping and banishment; the remainder, both men and women, to public penance and attendance upon the execution of their more prominent brethren. Upon one young man, whose tender years alone saved him from the flames, a sentence of a somewhat255 whimsical character was pronounced. He was to be suspended under the arms during the auto-da-fé of his brethren, and, with a halter around his neck, was from his elevated position to witness their agony, as an instructive warning of the dangerous consequence of persistence in heretical errors. Mangin's house was to be razed, and on the site a chapel of the Virgin erected, wherein a solemn weekly mass was to be celebrated in honor of the sacramental wafer, the expense being defrayed by the confiscated property of the Protestants.

Neither in the monasteries to which they were temporarily allotted, nor on their way back to Meaux, did the courage of the "Fourteen" desert them. It was even enhanced by the boldness of a weaver, who, meeting them in the forest of Livry, cried out: "My brethren, be of good cheer, and fail not through weariness to give with constancy the testimony you owe the Gospel. Remember Him who is on high in heaven!"511511 The hero of this action was of course arrested. Crespin, fol. 120.

Their execution.

On the seventh of October, Mangin and Leclerc on hurdles, the others on carts, were taken to the market-square, where fourteen stakes had been set up in a circle. Here, facing one another, amid the agonies of death, and in spite of the din made by priests and populace frantically intoning the hymns "O salutaris hostia" and "Salve Regina" they continued till their last breath to animate each other and to praise the Almighty Giver of every blessing. But if the humane heart recoils with horror from the very thought of the bloody holocaust, the scene of the morrow inspires even greater disgust; when Picard, a doctor of the Sorbonne, standing beneath a canopy glittering with gold, near the yet smoking embers, assured the people that it was essential to salvation to believe that the "Fourteen" were condemned to the lowest abyss of hell, and that even the word of an angel from heaven ought not to be credited, if he maintained the contrary. "For," said he, "God would not be God did He not consign them to everlasting damnation." Upon which charitable and pious assertions of the learned theologian the Protestant chronicler had but a simple observation to make: "However, he could not per256suade those who knew them to be excellent men, and upright in their lives, that this was so. Consequently the seed of the truth was not destroyed in the city of Meaux."512512 Hist. ecclés., i. 33; Crespin, fol. 121.

Wider diffusion of the reformed doctrines.

Far from witnessing the extinction of the Reformation in his dominions, the last year of the life of Francis the First was signalized by its wider diffusion. At Senlis, at Orleans, and at Fère, near Soissons, fugitives from Meaux planted the germs of new religious communities. Fresh fires were kindled to destroy them; and in one place a preacher was burned in a novel fashion, with a pack of books upon his back.513513 Hist. ecclés., i. 33-35. Lyons and Langres, in the east, received reformed teachers about the same time; although from the latter place the pastor and four members of his flock were carried to the capital and perished at the stake. Even Sens, see of the primate, contributed its portion of witnesses for the Gospel, who sealed their testimony in their blood.514514 Ibid., ubi supra.

The printer, Jean Chapot, before parliament.

In Paris itself parliament tried a native of Dauphiny, Jean Chapot, who, having brought several packages of books from Geneva, had been denounced by a brother printer. His defence was so apt and learned that the judges were nearly shaken by his animated appeals. It fared ill with three doctors of the Sorbonne, Dean Nicholas Clerici, and his assistants, Picard and Maillard, who were called in to refute him; for they could not stand their ground, and were forced, avoiding proofs from the Holy Scriptures, to have recourse to the authority of the church. In the end the theologians covered their retreat with indignant remonstrances addressed to parliament for listening to such seductive speakers; and the majority of the judges, mastering their first inclination to acquit Chapot, condemned him to the stake, reserving for him the easier death by strangling, in case he recanted. An unusual favor was allowed him. He was permitted to make a short speech previously to his execution. Faint and utterly unable to stand, in consequence of the tortures by which his body had been racked, he was supported on either side by an attendant,257 and thus from the funeral cart explained his belief to the by-standers. But when he reached the topic of the Lord's Supper, he was interrupted by one of the priests. The milder sentence of the halter was inflicted, in order to create the impression that he had been so weak as to repeat the "Ave Maria." But the practice henceforth uniformly followed by the "Chambre ardente" of parliament, of cutting out the tongues of the condemned before sending them to public execution, confirmed the report that Maillard had exclaimed that "all would be lost, if such men were suffered to speak to the people."515515 Hist. ecclés., i. 34. Occasionally, instead of cutting out the tongue of the "Lutheran," a large iron ball was forced into his mouth, an equally effective means of preventing distinct utterance. This was done to two converted monks, degraded and burned in Saintonge, in August, 1546. A. Crottet, Hist. des églises réf. de Pons, Gémozac et Mortagne, 212.

258

| « Prev | CHAPTER VII | Next » |